Animal Abstraction, Roger Ballen at Quality Pictures

The intrinsic nature of photography is confounding. Picked apart, the latin translates directly, meaning "light drawing". Caught from light particles bouncing off the objects surrounding us, the history of photography's purpose was the capture of those particles on light sensitive emulsions, and the result was the precise emulation of the world around us, so to speak. Due to the nature of this process, most of the world's audience considers the photographic image a small but somewhat accurate piece of reality. In the world of art, of course, the journalistic responsibility to depict one's surroundings with an attempted neutrality becomes null and void as the camera becomes an expressive tool. Images begin to tell the stories of an artist's priority and perspective. The incomprehensible proliferation of images in the modern world both raises the standards of the image quality and sophistication of realistic image making while also emancipating photography as a pure art form. This notion brings us to the most recent works of South Africa-based photographer Roger Ballen being exhibited at Quality Pictures until the end of this month.

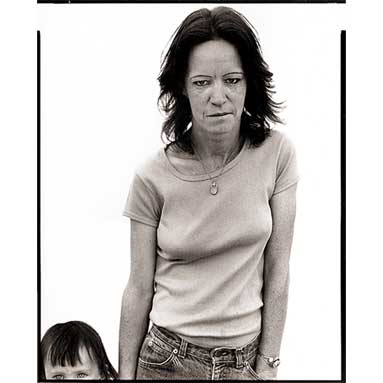

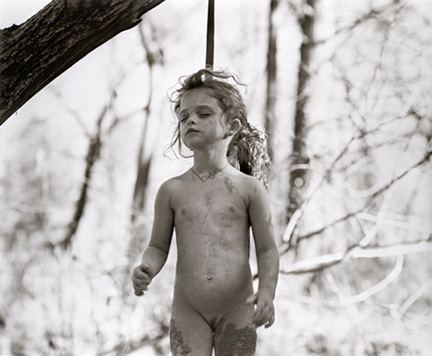

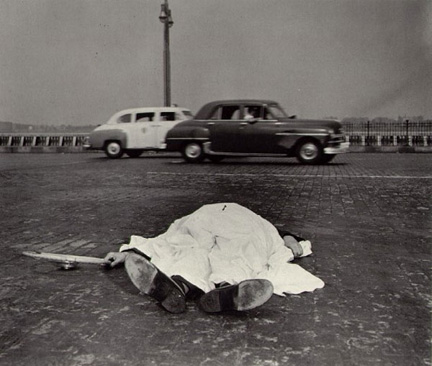

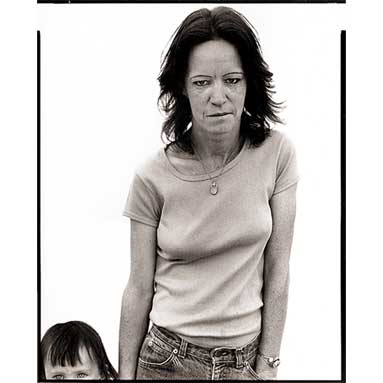

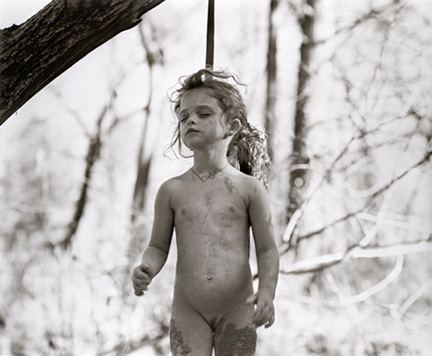

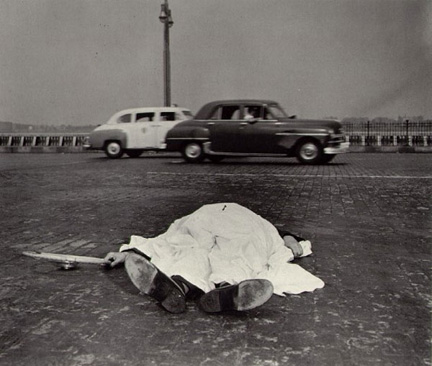

While at once working in the tradition of greats like Richard Avedon, Sally Mann, and photojournalist great WeeGee, Ballen departs from the documentary -esque portraiture and empathetic romance of the human condition to explore more expressive pastures.

Debbie McIntyre, Practical Nurse and her daughter Marie, Cortez Colorado 1983, taken from Richard Avedon's Texas

Photo from "Immediate Family" Sally Mann 1990

Weegee Photo excerpted from collection of crime photos, New York city ca. 1940's

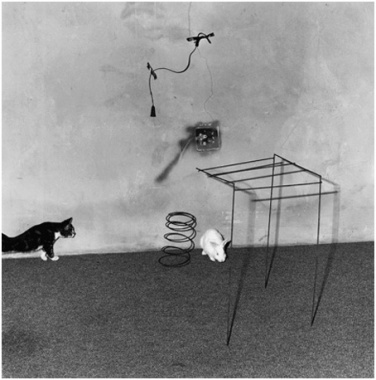

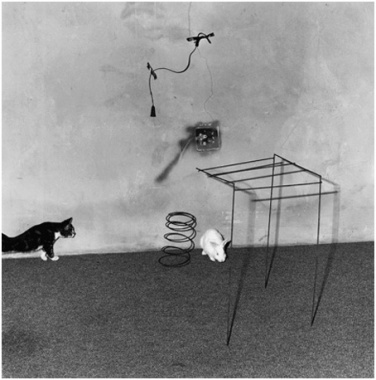

Walking through the gallery, Ballen makes clear his attention to the form, and as dark as the subject matter may seem to be at first glance, there is a pronounced feeling of play in an almost Dadaist sense. Yet this play is grittier, less movement-y, and more centered on Ballen's individual ideas. This work is more drawing than photograph as Ballen flashes his backgrounds so hard to blow out and flatten the space entirely, thus creating collages of his subject matter. Compositionally, they recall the drawings of the late Eva Hesse.

Eva Hesse, Untitled 1965

The clues Ballen gives the viewer to the identity of his subjects is almost nil, and their resulting quality of timelessness is the souffle born of these ingredients. Herein lies their magic. The compositions are sophisticated and beautiful and when combined with their subjects, darkly funny. Ballen plays the part of edgy and theatrical composer, mad painter. Yet when asked in an interviews about his process, Ballen becomes rather vague and even waxes philosophical in reference to the interrogation of what is spontaneous and what is staged. When remembering that his subjects are indeed actual people, imagining his process becomes somewhat strange and ridiculously arty. In an introduction to his book "Outland" 2001 (Phaidon), the experience of viewing his subjects is described as the following: "One is forced to wonder whether they are exploited victims, colluding in their own ridicule, or newly empowered and active participants within the drama of their representation." The latter description is indeed optimistic, but not an impossible idea. However, the more time spent with these works, the more ironic their sophistication and well donedness. Ballen's humans subjects seem as much props as do the puppies and chickens and pieces of mattress hedging the corners of his compositions. While the lack of space and thus place grants the certain timelessness to these works, it also allows that Ballen may have very well taken these photographs within the confines of his own studio. This becomes somewhat annoying when considering these works as finished pieces. As constructions, they are more interesting simply because they are photographs, and the imagery of what might be a wheat pasted punk rock poster on a telephone pole in Liverpool or a Sigmar Polke painting is a construction made with real subjects.

Sigmar Polke, "Menschenbrucke", Detail 2005

These are images we consider to be from life and in this way must answer to different sorts of responsibilities for which Ballen no longer feels inclined.

So, one thinks about all of these issues and says, "So what?" National Geographic on acid is cool, beautiful, edgy yet experimental. After a bushel of books and decades of photography all of these subjects are perhaps Ballen's good chums, no different from any other artist working in the field of photography these days. Considered in this light, the viewer considers these works afresh, as painting and sculpture. The goals become more ephemeral, abstract, and perhaps theoretical. Still, lack lingers. One leaves the gallery with the sense that this newer vein of expression is the middle of a journey towards something more. As Ballen feels less and less responsible to be the voice of this population's condition or to play the role as its documentarian, he finds the liberty to become more and more so interested in his own voice.

I find it interesting that much of the criticism of Ballen's recent work lies in the fact that is difficult to tell exactly what one is looking at. Ballen's pictures prove that even those who are knowledgeable in the medium still regard photographs as agents of truth. Ballen has succeeded in taking pictures that instill a high sense of mystery and confusion and yet viewers still regard them as some sort of truthful record. Its in this territory, where others find fault, I find art.

Often it's the very intelligent form of irresponsibility that artists impart upon our world that makes their work so interesting and valuable.

Most everything but art has some sort of terribly pragmatic cause and effect chain of being that can rationalizes their existential condition. Art can be the gremlin in that machine and its why I like Ballen so much. He reminds me a lot of Paul Klee, who in addition to his more whimsical stuff liked to study somewhat freakish assemblies of characters and their peccadillos. He gave these works a special code and instructed his dealer (Thanhauser) that these works only be sold to only the most serious collectors.

Ballen and Klee would have seen eye to eye.

![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.portlandart.net/nav-commenters.gif)