James Lavadour

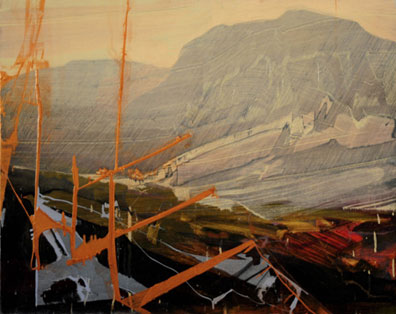

Star House, 2008

oil on panel

24" x 30

"The Master, spoiled with gifts of Heaven, suddenly appeared, demanding fresh silk to display his extraordinary art." The host gave a shout, 24 guests all stood up, and Chang Tsao strode into the room, sat down on the floor with his legs spread out, took a deep breath and then "His inspiration began to pour out. Those present were startled as if by lightning were shooting across the heavens or a whirlwind sweeping up into the sky. Ravaging and pulling, spreading in all directions, the ink seemed to be spitting his from his flying brush. He clapped his hands together with a cracking sound. Dividing and drawing together, suddenly strange shapes were born. When he had finished, there stood pine trees, scaly and riven, crags steep and precipitous, clear water and turbulent clouds. He threw down his brush, got up, and looked about him in every direction. It seemed as if the sky had cleared in a storm, to reveal the essence of the thousand things."

Fu Tsai relating an experience with Chang Tsao (699?-761)

We don't write about art like that anymore. To give this story some perspective, it was written 550 years before Chartres Cathedral, 800 years before Vasari would begin to record the lives of the artists of the Italian Renaissance, and 1200 years before the arrival of the nearest painter of our time that might meet that description, Jackson Pollock. Chang Tsao's art was about the transformation of the energies of nature into the energy of painting. His art was about the harmony of paint and the energy of the universe. In a typical Chinese way, the inner world of the artist reflected the outer world of nature, and vice versa. From Fu Tsai's description, Chang Tsao's paintings were not a depiction of a landscape but it was the energy of nature filtered through the hand of the artist that allowed the painting to be created by the rules and processes of nature herself.

I want to tell you a story about another artist who also found his voice by tapping into the energy of the fusion human experience and the natural world. Actually, I wanted to give James Lavadour room to tell his own story. He explained that at one time, he gone through seventeen jobs in seventeen years. With a family to support, I can't help but think that the struggle began to generate a lot of friction. You could say that the he tapped into an energy source, even if it was not the one that he thought he wanted. Slowly, over many years, the energy of his life became the energy of his paintings. He began to see his own energy reflected in the energy of nature that he experienced hiking in the mountains. One began to flow into the other. Here is his own story in his own words:

"I spent a lot of times in the mountains. I had grown up in the mountains because I had grown up on the reservation. I remember meeting these other young people who were encountering nature for the first time. It was the first time that I figured I knew something about something. We spent a lot of time in the outdoors just walking. It was when I realized that I had made a connection between what I was looking at and what was going on inside of me, in a physiological way.

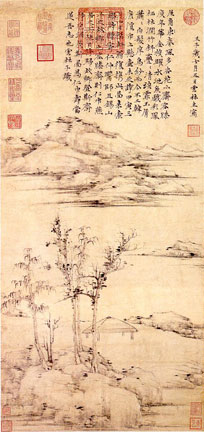

Li Cheng (919-967)

Scholars looking at a Stele

Ink on Silk

Where I come from there is the earth and the heavens, and we are made of the same stuff. The creator put the fish, the berries, the meat, and the water here to take care of us, but what of me is also part of nature? I approach nature as a way of learning about who I am and what I am. I began to collect my information about making paintings from the physical act of engaging with nature by walking or sticking my hand in a stream to understand what it is. Instead of looking at it, I felt it. You lay down on the earth and take nap on the hillside or you drink good water after exerting yourself on that hillside. All of those things become a part of your body memory, your muscle memory. Although you can't remember all of the experiences, you can unlock them by certain kinds of visual stimulus because seeing is a physical act in itself. Seeing is a physical thing. I began to understand the relationship between the stimulation of looking at something and muscle memory. How it unlocks a cascading type of memory where we remember things in a very limited way but once you start moving it floods. That is where I wanted to be in terms of making an image. I wanted to be moving.

Mark Tobey

Calligraphy in White

1957

In Walla Walla, at the time, there were a lot of Tobeyites. You know, people that worshipped Mark Tobey and had white writing everywhere. That was my beginning. I liked everything from Charlie Russell to Robert Rauschenberg. I was voracious about whatever I could see. A lot of the artists that I knew were regional artists. At the time, everybody was dropping out, the sixties kind of thing.

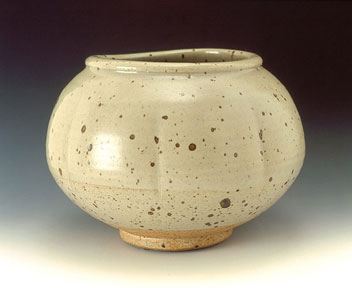

Mark Tobey reconfirmed my whole interest in Asian art because Tobey was a great lover of Asian art. He had a lot of non western friends who were Persian or Japanese. One was a Japanese potter named Hamada Shoji (1894-1978). Another ceramicist was Bernard Leech (1887-1979). They were both into the revival of the Folk Arts. Hamada was especially important to reaffirming my thinking about paint and pigment. His approach was astounding, you would see these little pieces and they were like the cosmos. They are wonderful things. When I experienced that microcosm of the cosmos, everything else just fell away. Tobey started down this path, but it was enough for me to feel like I got a glimpse of something.

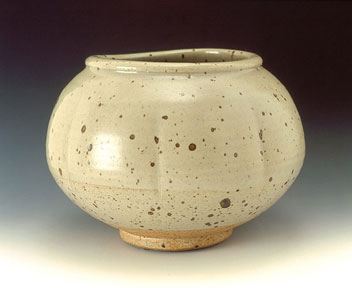

Hamada Shoji (1894-1978)

Cup

The landscape becomes part of you. I did not mean it to be farfetched, for me it was very practical. After the experience with Tobey, I began to discover other artists who had worked from the same starting point which were the Chinese painters. I fell in love with the Chinese landscape painters. There was a book that was published in the late eighties called Symbols of Eternity: The Art of Landscape Painting in China by Michael Sullivan. The book describes a brief history of the long process of the development of Chinese painting. One of the ideas is that Chinese painters were very much interested in the organic principles, or the embodiment of nature in paint. It is about bringing the cosmos down where you can look at it on a piece of paper just made sense to me.

They could deal with the cosmos with a simple line, you have the heavens and the earth right there, divided by a single line. Then I ran into other artists like Max Beckmann who said "If you loved nature with all of your heart then new and unimaginable things in art will occur to you because art is a transfiguration of nature." That whole process and that whole way of thinking was really what I was after.

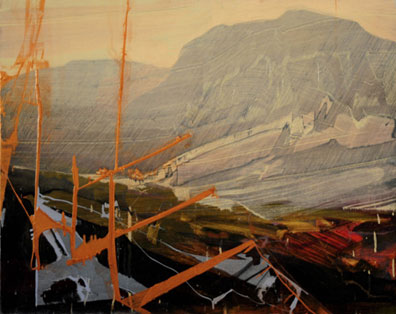

James Lavadour

Sputnik, 2008

oil on panel

24” x 30”

My main interest has always been about the properties of paint, what paint does. One of the things that paint does is that it is organic and does the same sort of things that dirt does, anything in the natural world does. It has the same processes: erosion, sedimentation, flow... I saw in that microcosm of a landscape. I saw the same processes in watercolor settling in on a piece of paper as rivers and mountains. That was the first principle that struck me early on and I realized that ever since I was a child I was fascinated by those particular processes.

It was not too far from pouring paint on canvases causing erosions and actually making landscapes. Then, I had to figure how to control that process by developing certain structures that came out of walking and just moving your body. The whole physiological aspect of moving on a piece of land and how that influences your physical motions and how those motions bring your body into the landscape. When you move your arm in a certain way, it causes all of these events to happen. That is how I started my whole landscape theory. It is a fairly simple process, putting paint on a piece of canvas and scraping it, stretching it, layering it and all of those things. It is not rocket science.

James Lavadour

Platform, 2008

oil on panel

24" x 30"

I realized that I had two basic things that I work with in my paintings: the first is organic flow which is the landscape. The second was an architectural grid or abstraction which is based on the human perception or response to the natural world. Those two ideas have always been my right hand and my left hand. They were polar opposites of one another. I used to do either abstracts or landscapes. At this point, they intersected in this collision. After that I had no idea what was going to happen then. The abstracts became more like landscapes and the landscape became more like architectural structures with a cellular structure that had spaces within spaces within spaces.

I think of painting as something that I started way back when I was a kid and I am doing the same thing now. I am thinking about the same things now that I was thirty years ago. A lot of the times when I am working I am come across elements of a painting I worked on thirty years ago. I can almost remember the exact moment that I discovered or understood a process for the first time. It is a very strange wonderful experience where you can have those flashbacks. It is like timelessness, it is the experience of your life not really having a sense of time about it.

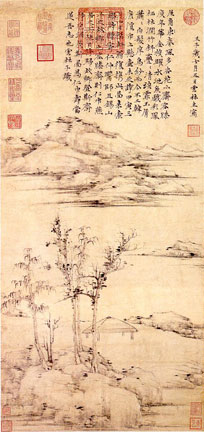

Ni Tsan (1301-1374)

Jung-Hsi Studio

Ink on Silk

The body of work is a flow of energy. It is not a picture and it is not a landscape. It is a flow of stuff. I am always trying to either straighten it out or mix it up. Sometimes it is flowing along and you want to break it up and sometimes it breaks down in vortices and turbulence which is just things within things within things. If you get stymied there, how do you straighten that back out again to a more directional flow.

Then I learned other things like when I met Norman J. Zabusky who gave me a whole different way of looking at what I was doing just through the physics of flow. He is a scientist who works at Rutgers University. He described one of my paintings one time in scientific terms. So rather than drips it was fingering instability. He just went through all of these terms of Physics like fingering instability, flow and cosmic vortexes. That was all I needed to start looking at my painting and leave the language of it behind. I was allowing myself to become fluent and fluid at the same time, realizing that what I was doing as an artist was expressing energy. To paint is a multifaceted activity. It is not just one thing or working at one level. You are using your muscles, your mind, your heart and your ears that each have their own strata. It is not just one thing. It is in motion and I began to see my body of work not as one painting at a time but that I am working with the energy of an entire body of work.

James Lavadour

Blast, 2008

oil on panel

24” x 30

Aesthetics are more like habits. Habits become a hindrance after a while. I am always trying to break my habits even though I have very simple structures. Some people have said that I do the same painting over and over, and in sense that is true because I am using certain kinds of universal structures. In the science of flow, everything moves until it encounters an object. When it encounters an object then it splits apart and creates a vortex. Eventually, the vortex begins to break down and creates turbulence which is just vortices and bubbles.

When I used to work, I used to add all of these things together at one time and I did not know how I got from point A to point B. When I started making prints when I went to Rutgers University,I worked with a lithographer. When you work on prints, you are challenged to be more analytical of what you do, about how to understand your own process. I realized that I did not understand my own process. I was thinking more emotional, psychological and pure luck. Because printmaking is one layer at a time, I had to understand my process one layer at a time.

Bernard Leech (1887-1979)

Bowl

This was when I started listening to Jazz, and the improvisational process. The way that a group of musicians from all over the place get together in one spot and make music. If you listen to Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane or any of those people they are all strong individual musicians. They are all doing a particular thing and they are moving in and out of one another, countering one another or wrapping around and opening an opportunity for another musician. I began to think that was the perfect way of thinking about making an image, especially in printmaking. Printmaking is totally painful for me and it was excruciating to have to slow the process down. Once I began to understand the language and the process of it, that knowledge really opened my productivity. I could take what I was doing and separate it into stages over a period of time instead of having my whole emotional investment at this one moment where if it does not work out, I am crushed.

It was like when I was listening to John Coltrane. I listened to a lot of music and Coltrane finally came to a point where he had deconstructed Western music. He pushed it to such extreme that it became a question as to where to go next. Then he ran in to people like Ravi Shankar, Ornette Colemen, and more African musicians. With his horn man Don Sherry they started travelling all over the world where they started collecting all of these different ideas about music. For me it was like art making, where it is really alive and universal. That was one thing that really excited me about his process was the universality, where art, like music, was beyond language.

James Lavadour

Bank, 2008

oil on panel

12” x 18”

I was able to take all of the emotional aspect out of the process and setting it over here, it is always going to be with you anyway. You have to able to detach yourself from the process and spread it out to let the patterns appear just like what Coltrane talked about. He said that it is just vibrations and his goal was to put it all out there and look for patterns. Look for melodies. That is what I did in a lot of ways. I took what I did and broke it down into its basic elements and started looking for where they flowed together. I was looking for where the energies intersect. How one layer creates depth and one color effects another or how one image affects other images in cases with multiple panels.

I start from a very simple starting point like a single layer of paint with a monochromatic palette. I was interested in the properties of the paint more than the image. I figured out different ways of manipulating the paint which led to a certain kind of structuring of those processes. I spent a long time just studying that single layer of paint without knowing how to get below the surface. But now, I am above and below the surface at the same time. It is much more dimensional.

James Lavadour

Fog, 2008

oil on panel

12" x 18"

Usually, I start with a color. I have not started any new panels in three or four years. I have just been working on things that I started several years ago. But I usually start with a yellow and when it is still wet I might put a red linear structure into the space. I might also mix a green into it. When it is all still wet I might start scraping into it and then letting it dry. It does not have any form to it yet, it just has a dimensional mass. I might do dozens of panels all at once with a few variations. I just let the palette evolve until it starts shifting. You get bored of one thing and so you pull in something else. That whole process takes time to build up hundreds of those panels. Every once in a while one of those might be close to a finished piece.

It is more like being a Jazz musician because you are responding to all of the previous layers. After the physiological scrape where you are not thinking about what you are doing, at the next step you are looking at what you are doing and how do interact with the pervious actions? How do counter or balance what is already there? What color approach are you going to use this time?

Hamada Shoji (1894-1978)

Bowl

Then the painting becomes dimensional. The first layer is about physiological expression, but after that you begin to deal with time and structure. It is about the geology, the architecture of painting. You become more cognizant and aware of your experience. You are always trying to get the most out of the least effort rather than blasting it each time. Paint is beautiful and it has its charms no matter what stage it is at, so you want whatever it is producing at the time to be visible through successive layers of time.

I have the ambition, energy, and ability right now just to paint. I have worked for that for a long time. I can unplug the phone and nobody comes around for days, maybe weeks at a time, and so I just paint. Keeping yourself going and keeping it flowing is more difficult than it sounds. I am always learning some new device to show me how to do that. Sometimes things naturally play out. You have a process and it is not complicated. It serves a certain function in that it gives depth to what you are doing but in itself it is not that interesting.

James Lavadour

Smoke, 2008

oil on panel

24" x 30

What I am working on now is work that I started in 2000, which I saw as this big explosion of energy where all of these little pieces are just smaller expressions of the same energy. I could work on one and the go to the next and then the next one after that and so on until I slowly came back to where I started and then the whole process keeps repeating itself. It has been about nine years that I have been working on this body of work. First it was like this huge explosion of energy and then as it started to come back it started to compound like layer upon layer upon layer which created new problems.

Sometimes, the painting gets you to a point where you could see in many directions. The artifact itself, you get beyond it, it is consumed. It serves it purpose in being able to being a conduit to many other things. It might allow you to hook many different layers together but in itself it might not be the greatest thing you have ever done. But for you the kernel of a great experience was there. I always want to get those things back and just keep working on them. But you can't always do that. Galleries are sometimes difficult like that. Anything that you want to know, anything you want to achieve, doesn't come from someone giving you an open door or praise or anything, it is in your work. Praise is good and makes you feel good. If it motivates you to work more, that's good but it is not more important than the work.

James Lavadour

Scaffold II, 2008

oil on panel

24" x 30

A lot of the times I connive with, or against, my gallery about how to get work back so I can work on it. A lot of the times it is not worth the effort, but sometimes it is. That is what this show is for me, these are paintings that I have been working on for the past nine years. Some of these have even been shown before and I got them back so I could work on them again.

It is like you are standing in one spot and whole universe is swirling around your head. Sometimes it is hard to tell where you are. It is terrifying. A lot of times, I get up at 3:00 am and paint. There is something about the energy of that time of day that is important to me. It is easy to get right to the very edge of perception at that time with no distractions. It is a terrifying place, it is not always a good place. It is a disturbing place, once you see through something it is difficult. It is all just neutrinos or it is all just vibrations."

In a word, the paintings are about energy. The energy of our lives, the energy in the landscape, the energy in the difficult situations that we sometimes have to confront as we grow in life. It is about letting the paint do what it does. Lavadour has a way of finding harmony with the medium so that when he translates the experiences of his life into the work it is there naturally, spontaneously, almost effortlessly without any interference from himself. For him, painting has become an efficient form of filtering through his experiences in nature and the geology of the landscape. But he can't depict the event or even will it to happen. It has to appear on the panel naturally, maybe almost in a forgotten way. I think that is why he works on so many panels at one once, he has to find new ways to lose himself each time. The paintings have to be more than the limits of his own ideas.

The simple is lesson is that we are not separate from experience of our lives, just as he is not separate from the work which is not separate natural world. They are all reflections of one another. The paintings are never a depiction of anything. To depict or represent something means that you are working with a painting with a preconceived idea or that you are know what you want. In Lavadour's case, it is because he needs to learn and experience what they are about, he needs to discover the paintings along the way. It is a process that allows for both that artist and the work to grow together.

James Lavadour

Under Fire, 2008

oil on panel

24” x 30

When his process works, the painting can appear naturally and spontaneously without any extra effort on his part. The repetition is a way of loosing himself in the process, to let the natural properties of the paint take over and lead to the next step. That is why he is able to work on panels over a series of years. Each panel becomes ripe in its own time in its own way and not before he or the panel is ready for it. They have to grow together before they know what they are about. It is a patient process but it gives both the artist and the work plenty of time to change, grow and experience before it is complete. It is a dynamic process that is open ended and on going.

The rhythm of panels is important so that not any single one is precious. The sheer numbers of the panels that he starts at any one time is not about some overdriving of ambition of what he would like to do with his paintings, but as a way of taking himself out of it one panel at a time. Lavadour has never felt comfortable in the art of the western world. Perspective and color theory have never held much interest for him. The theories have only been a way from separating you from what is important, the experience of the present moment. They are about thinking and not feeling. In his painting, he is not depicting the landscape, it is its own landscape in the language of paint. More importantly, he does not want you to look at the painting, he wants you to be in it. He wants to give you the opportunity to experience it the way that he sees it. To be able to touch and feel the contours of the land in the way he uses a brush. To paraphrase Pollock it is not about nature, it is nature. Each painting is a microcosm of a much larger cosmic system. The paintings are life, our lives.

James Lavadour

Yellow Fire, 2008

oil on panel

12" x 18"

Each painting is a like a koan about how fit into the world, how do we see ourselves in the land? The answer is that one effortlessly blends into the other. We become the landscape the landscape becomes ourselves. Rather than polar opposites, we are simply different sides of a continuous spectrum. Through his paintings we learn that we are not only not separate from nature but that we could not separate ourselves from nature even if we wanted to.

He is there working on it, every morning before the sunrise, practicing his art. Perhaps it is no surprise when I asked him if he had any advice for younger artists, his answer was "Work. Work. Work. Work. Paint. Paint. Paint."

James Lavadour's Close to the Ground at PDX Contemporary Art, April 1-26, 2008

![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.portlandart.net/nav-commenters.gif)