|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

Camouflage at Portland Art Museum  (L to R) works by Philip Taaffe, Andy Warhol, Agnes Martin and Damien Hirst (photo by Dan McLaughlin) The universe is stuck in a rut, be it the motion of the planets, the behavior of subatomic particles, the cycle of life & death or the ebb and flow of freeway traffic… everything tends to follow some predictable patterns. Yet the patterns of life, be it the movements of the sun or the coordinated acrobatics of flocking birds are so pervasive that they often become invisible to us… unless something provokes a pause rendering them visible once again. Art can achieve that perceptive pause. How poetic is it then that this small show at the Portland Art Museum with major works (many on loan from the Broad Art Foundaion) exploring the use of pattern in Post WWII art is called Camouflage?  Damien Hirst's The Kingdom of The Father gets Scout Niblett's undivided attention With works by Agnes Martin, Christopher Wool, Philip Taaffe, Damien Hirst and Andy Warhol it is small but heavy hitting sampler of a major trend in postwar art. Truth is pattern is hardly a recent trend; it's a pervasive human impulse to create visually discernable patterns. From Scottish tartans to Maori tattoos or the metal cladding on a Frank Gehry building, pattern never leaves our visual vocabulary. That's why modern art was originally so radical; it very consciously sought to change the visual fabric of Western Civilization (partly by borrowing from non western sources). Modern art made a case for the removal of extraneous pattern or ornamentation and explored an aesthetic shift paralleling the new visual rhythms of an industrial age. Later, as the cause of modernity became style, pattern became unshackled from any specific duties, exiting purely out of habit as the ultimate existential visual athlete. Early on an important father of modernism, Fin de siecle architect Adolf Loos sought to strip architecture of perfunctory ornament and published tirades like, "Ornament and Crime" where he equated extravagant ornament with primitivism and superstition. Back then pattern was emblematic of social order and it still is today. Yet, in the USA it is rarely talked about outside of design oriented circles. Thus, modern art didn't get rid of pattern all together, instead it typically preferred patterns that revealed its means of production or industrial ties (a la a Pollock drip, a Duchamp's coat rack, Sol LeWitt instructions or Donald Judd's serial fabrication). In this way modern art replaced the ritual of tradition with the industrial rites of production. In the cases of LeWitt, Joseph Albers, Mondrian or Judd each artist seemed to possess a kind of underlying production algorithm for pattern… in the case of LeWitt he literally created the algorithm or instructions and let others take a hand in producing the art. Though hardly a comprehensive survey each artist in the Portland Art Museum's Camouflage show addresses recent rituals of pattern. Each artist posesses a unique set of goals and effects that explores and deepens our enduring fascination with repeating visual forms.  Warhol's Camouflage (1986)[top], Agnes Martin's Untitled #13 [bg] and Christopher Wool's I Smell a Rat [fg] The eponymous work of the show, Andy Warhol's Camouflage at 37 feet wide could render most walls invisible but in this show it is mounted at least 11 feet off the floor on an expansively tall wall in a huge space designed by Pietro Belluschi (who was following Loos' only slightly earlier lead). The effect of such a hang hints at the religious but instead of an experience like the Last Supper we are confronted with a militaristic pattern designed to obscure whatever it covers. In today's context it is an incredibly wry use of pattern and space as The United States seems to be caught in a war pattern of its own. To my cynical eye the pattern of war only seems to produce more war. Similarly the camouflage pattern itself is repeated 5 and a half times and its mechanical reproduction ironically parallel's the dehumanization wars always seem to spread. The painting is also one of the last executed by Warhol who was best known for his silkscreen portraiture of celebrities. Warhol once even stated he'd like to be a machine and maybe in this one case he has achieved it. When I view this piece I don't consider it a product of Warhol's persona seeking out other personas M.O. Instead, I see a militaristic pattern and self fullfilling prophecy. It certainly fits in with Reagan Era cold war arms spending. Still, Camouflage reads different today as the military isn't just an expenditure that consumes money. It consumes human life and the camouflage feels too cool, too clean and to reproducible to trust and it's a sad, uneasy testament to Warhol's work that it continues to feel so relevant today.

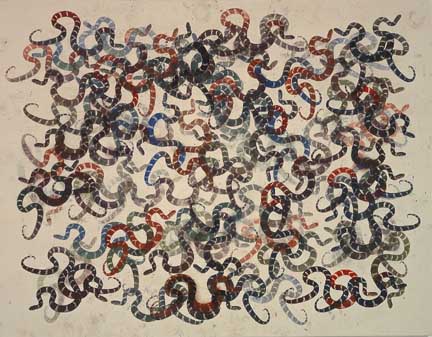

Philip Taaffe, California Kingsnake (Ringed Phase), 1996-97. Mixed media on canvas. 91 ¼ x 117 inches. The Broad Art Foundation, Santa Monica. The work of Philip Taaffe is a cousin to Warhol's use of mechanically reproduced images and is even more intensely interested in pattern. In California Kingsnake (Ringed Phase) the snakes are screened over and over again with skins that phase through the ROYGBIV color wheel, yet another form of pattern. I particularly like how the snakes have been screened onto the other side of the canvas, bleeding through to the surface. The net result is ornamental but so thoroughly so that the reproduction of the snakes becomes rythmic, giving these very man made reptiles a convincing naturalness that merely 2 or 3 images could not have convey.  Bathyllipsis (detail) courtesy of the Broad Art Foundation The other Taaffe in the show is Bathyllipsis, which sports fuchsia, white, teal and baby blue arcs. Though painted in 1995 it simply screams the 80's to me. I dislike this painting but somehow I can't stop thinking about scary 80's things like friendship pins, Automan and the Thompson Twins etc. in front of it. Funny how certain patterns and colors can be so indicative of a certain time. It's too bad there weren't a few more Philip Taaffes here that explored different eras like his explorations of middle eastern patterns etc. Over the past 50 years he's definitely become a key pattern artist.  Wool's Untitled (1988) courtesy of the Broad Art Foundation Similarly, another painting that seems to have crossed the line into pure style (which by no means invalidates it) is Christopher Wool's Untitled from 1988. The pattern is beautiful, cold and utterly opaque in a way that makes the Warhol and the Taaffes seem warm and fuzzy. Here the pattern is self replicating means to itself. This is art that has backed itself so far into a cynical corner it becomes generous and open ended… It's the sort of work that only could have occurred during the end of the 80's.  Detail of Untitled Wool's somewhat later painting in the show, "I Smell a Rat" feels soft by comparison to Untitled but it's also more street as it replicates some of the layer upon layer accretion of graffiti art stencils. It is almost a form of street art reduced to meaningless territorial heraldry. Im not completely convinced by this work but some like Jerry Saltz swear by it. I much prefer his stenciled word series but they don't fit into this exhibition's subject matter. Maybe this is the painting that questions the inherent "mere decorative" suspicions one always seems to encounter in pattern oriented art? Still, decoration in the hands of an artist like Wool is more than just an affectaion.

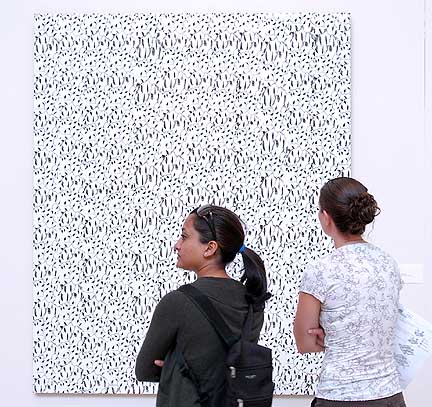

Damien Hirst's The Kingdom of The Father (2007) courtesy of the Broad Art Foundation As the master of late 20th century and early 21st century presentation art Damien Hirst seems to take the lessons of Warhol, Judd and Bruce Nauman while infusing them with all the presentation savvy of a major PR firm obsessed with mortality. Finally, we have an artist who seems more formidable than a multinational corporation. Yet, Hirst's work goes beyond slick pitch perfect art propaganda. Hirst's latest major work to be revealed publicly "The Kingdom of the Father" shows just why those shocked by his prices or celebrity have latched onto a red herring; this piece routinely stops people in their tracks utilizing little more than pattern, butterflies and ecclesiastical window dressing. Consisting of three arched panels filled with butterflies and moths, the dead insects create obvious references to stained glass windows like those at Chartres cathedral as well as referencing Matisse's Barnes foundation murals. Is it possible the "Father" Hirst is referencing in the title is Matisse not a Christian God? That thesis is further supported by the use of Blue Morpho Didius butterflies in all three panels that were very important to Matisse. Before Matisse fully developed as an artist he spent his entire month's budget on one of these blue butterflies and his late cutout work often pays homage both to their color and delicate nature. Matisse was a master of pattern as well and perhaps Hirst is making both a sly joke about the power of beauty, death and art history while being sincerely interested in the final effect; inspiring awe through death.  The Kingdom of The Father (detail) For every dismissive half-interested journalist who slags Hirst for being flashy successful and generally unaffected by whatever they write here is a piece which overshadows the persona of its creator. Sure, other artists like Jean Dubuffet have used butterflies before but by creating such a jaw dropping display of pattern, steeped both in death and beauty Hirst uses the visual languages of science and religion to nullify one another. Hirst is an artist who sets up stalemates between an overload of visual presentation and conceptual questions that cannot be answered… what technique is better than pattern to convey such hermetic loops of information?

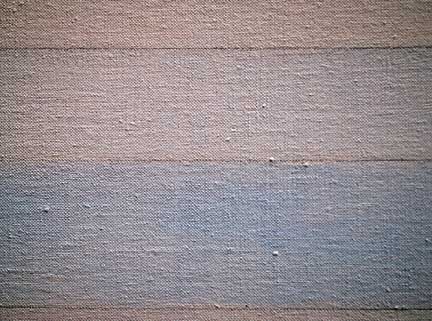

(fg) Agnes Martin's Untitled #3 (1984) Courtesy, Miller Meigs Collection The work of Agnes Martin, though visually the quietist work in the show, best exemplifies the personalization of ritual as a way to produce pattern. Her paintings exist as an outward example of an internal practice. For example, her untitled #3 consists of numerous grey horizontal stripes. Each stripe was painstakingly created by repeated applications of very thin acrylic paint, allowing the acrylic to permeate thoroughly the fibers of the linen support. Thus, the finished painted pattern isn't just a surface treatment it is a record of the very ascetic accretions it was created by. This high level of internal and external consistency shows how pattern can bestow a sense of legitimacy, acting as an analog for commitment.  Detail of Agnes Martin's Untitled #13 (1980) Another Martin, the gorgeous Untitled #13 is more delicate than Untitled #3 and its graphite lines separating incredibly nuanced acrylic paint stripes give it an almost middle eastern air. Neither #3 or #13 is fussy though, the patterns are expansive, patient and careful. Agnes Martin's work makes a case for pattern as an analog for wisdom. This shouldn't be surprising as Martin, Hirst and Warhol are all artists whose personas cannot be separated from their work. In fact, their work tends to deepen the viewer's respect for their personal process while mere descriptions come up short and often provoke cynicism. Maybe that is why Martin, Warhol and Hirst are all artists of the highest order and other pattern artists like Taaffe, Wool, Chris Ofili, Alex Grey and Ryan McGuiness though good, aren't likely to reach the same heights. The fact remains that pattern, rather than being a smokescreen can also translate or reveal worldviews and represent hermetic practices as a hueristic gestalt. As an opportunistic sampler show Camouflage is satisfying as a conversation opener but one wonders what a more thorough show also including the likes of Gilbert and George, Joseph and Anna Albers, Klee, Mondrian, Jessica Steinkamp, Karin Davie, Judd, Matisse, Jackson Pollock and Yayoi Kasama would have been like? Still, for a city hungry for serious contemporary art seeing work by Warhol, Martin, Taaffe, Wool and a new Hirst in an intellectually coherent show definitely shows just how much more exciting the Portland Art Museum's programming has become. Camouflage, curated by Bruce Guenther is definitely revealing a new pattern at PAM and Portland in general. The universe may be stuck in a rut but the best art isn't. show runs through November 4th 2007 Posted by Jeff Jahn on October 17, 2007 at 9:30 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |