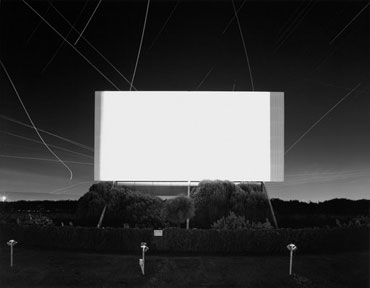

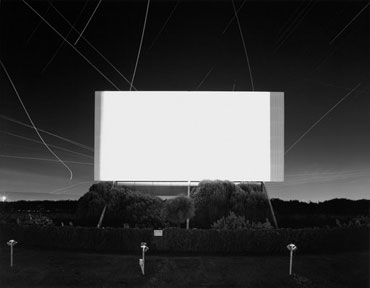

Hiroshi Sugimoto Union City Drive In, Union City 1993

Photography is, by definition, about the interaction between time and light. In Hiroshi Sugimoto's photographs we are able to engage in a conversation with light. In a very real way, he opens the light to us. He lets the light speak to us in a way that would be impossible in any other medium. Sometimes the light is fast like in the Seascapes and the dioramas where the exposure time is some small fraction of a second. In other work the light is slow, so slow that one photograph is exposed for the length of an entire movie. In most of his photographs the light is reflected, so that the light seems to be emanated from the subject that he is photographing. This gives the dioramas, the wax figures and even his Sea of Buddha series an uncanny, life-like feeling as if the figures only settled into position a split second before he clicked the shutter. We feel the life of the objects that he photographs and not the hand of the photographer. He heightens the interchangeability between time and light in a way that gives his photographs a remarkable presence. Whether he is looking at animals, the plaster cast of a mathematical formula or even on a cliff high above the ocean, you can sense that he begins to learn about an object by the way that it interacts with light. The Hiroshi Sugimoto Retrospective that is currently on display at the De Young Museum in San Francisco until September 23 is a record of the themes that he has explored for the last thirty years.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Pine Landscape 2001

The ideas that run through his work have been remarkably consistent over his career. The subject matter might have evolved but his search for the essential and eternal in a variety of forms has never changed and this has given Sugimoto's photos a character that is so different than the work of other photographers. In most photographs, you can feel the hand of the photographer arranging or framing the scene in a way that would make the composition most interesting. Sugimoto works in exactly the opposite way. The compositions are almost always dead on, so the form and not the photographer is revealed. They are engaging because by eliminating composition or any sort of technical tricks, they leave room for the viewer's own experience. At every turn, he is always trying to take himself out of the photograph, to let the place or the form speak for itself. In this way, he reminds me a little of Jasper Johns, who also uses the things that surround him as ways of exploring ideas about himself. His photographs come out of a different place than most photographers, and that is why he has found such a large crossover audience in people that are not usually interested in photography.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Mathematical Form: Surface Model 0006 2004

All of the photographs in the show are black and white, except for one that is based on a painting by Vermeer. Black and white photography is a medium that highlights that feeling of light and tonal depth as well as being an abstraction of reality. Each photograph is a construct, and Sugimoto reminds you of this every time you look at a one of his works. He is different than most photographers in that he is not illustrating an object for the viewer, but he is creating the parameters for the viewer to discover their own experience in interacting with an object.

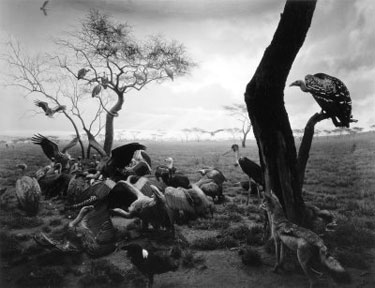

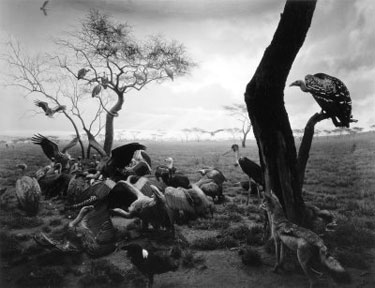

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Hyena-Jackal-Vulture 1976

I think that is why Sugimoto found the dioramas at the Museum of Natural History in New York so compelling. The dioramas are a recreation of an animal and a small part of its natural environment that usually includes some sort of narrative tension that adds drama to the scene. Of course, the tradeoff of this kind of exhibit is that the animal is no longer alive, they are stuffed, and so that you can always feeling the human hand of the curator framing nature for you. The animals might live on land or on the water, they might be modern or they could even be prehistoric. Each exhibit is its own bubble of time and space and although it is completely artificial, the best capture some essential quality of the habitat and the animal. The stuffed animal does not need food or water, and so they have become, like the Egyptians, immortal after death. I think that Sugimoto likes the stage set quality of these exhibits and at some level he realized that through the eye of the camera, and with appropriate lighting, the dead can come alive again. The camera can animate the inanimate, it can bring life where there wasn't any before. His photographs of the diorama become like a time machine and we can ride along with him.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Henry VIII 1999

It should come as no surprise then, that as we walk through the galleries at the De Young that he becomes interested in photographing the wax figures that you might come across at places like Madame Tussaud's, where you can see not only famous personalities of the past but also the famous celebrities of today. Again the models, although they are meticulously arranged and lit, are always lacking a soul and are therefore supernaturally still. But because a photo is only a depiction of a fraction of a second of time, there is something of the life of these people that comes through in his photographs. I have heard stories about how when he was working on the portrait of Anne Boleyn he worked on the lighting for hours to make sure that each pearl on her necklace was carefully and individually lit. He is able to capture some of the spirit of life, without the fragilities of life, and under the right circumstances, these figures might look the same way in a thousands years as they do now. I think this is the quality that appealed to Sugimoto most, it was something that would be here long after we are gone, maybe even something absolute and eternal. They could be permanent. I am reminded of that line from the movie Blade Runner, "more human than human." He captures the essential to make it transcendental, but only by eliminating everything that makes us human.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Anne Boleyn 1999

I enjoyed the way that Henry VIII and his seven wives were displayed in descending order with Henry himself at the top of the pyramid. There was something funny about the presentation because it was like looking at a family tree of real, or wax, people. But then again, maybe that this how Henry saw himself as king and everyone else fell into line below him. I was amazed at the beauty and the craft of these photographs. There is something about the light, the stillness or maybe it is the softness of the skin, that you could never mistake these people for being real. They really do seem to be "more human that human," all of our potential and none of our weaknesses. The wax figures embody something of the affection that some Japanese people have for dolls. They are beautiful but they lack a soul so there is a tragic quality that permeates the experience. The doll becomes an exquisite hollow shell. In this way, Sugimoto has more in common with Takashi Murakami than you might expect because they would be both be interested in inhabiting the uninhabitable, whether it is anime characters, robots or wax figures.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Boden Sea, Uttwil 1993

There is an obsession with timelessness that runs through his photos that is made even stranger by the fact that the photography is an essentially temporal medium. In his photographs, the light literally reveals the passage of time but sometimes in a photo, rather than being a fraction of a second, sometimes you can feel a millennia slip by and we are transported to another time and place. Sugimoto wanted to take a photo of a landscape that had not changed in over a million years. There aren't any mountains that look the same today as they did a million years ago. Landforms are eroded by wind and rain or created again by volcanic activity. But although the volume of the ocean has fluctuated over a million years there are qualities about the ocean that are eternal and in this way the seascapes have an unexpected connection to the dioramas. In the seascapes he wanted to experience the distant past as well as the distant future first hand by concentrating on something that never changes, the horizon line of the sea.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Caribbean Sea, Jamiaca 1980

Sugimoto was not satisfied with photographing just one seascape though, and his idea at some point must have evolved. If he was initially attracted by finding something on Earth that is absolute, soon he felt compelled to travel all over the world to find unique characteristics of ocean's horizon line at each location. He felt compelled to photograph the ocean in different parts of the world like Jamaica, Japan, Sicily and England just to name a few. He also photographed Lake Superior, which I suppose is sort of an inland sea. It must have been strange for him to realize that the horizon of the sea which should have been the same everywhere, was different everywhere he went and that something that was so simple turned out to be so complex. Each of the seascapes is photographed so that the horizon line is at the center of each print. There are no ships or people or any other indication that would suggest a time or place beyond the title of the print. The Seascapes have a lot of variety and a surprising amount of individual character. The seascapes were my favorite part of the exhibition of the De Young. They were installed on a wall that slightly curves so that while you are looking at each Seascape you are always aware how the series evolves by seeing the other photos on the wall out of the corner of your eye. Since the composition is always the same, it is the differences that stand out and so I felt like the experience became like looking at a series of Agnes Martin paintings. Both Sugimoto and Martin, found a remarkable freedom and life in what could have been deadening constraints. In both cases, the life in these photographs did not come from inventing a new composition, but in letting the viewer experience what is right in front of them.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, North Atlantic Ocean, Cape Breton Island 1996

Each Seascape is the same. Each is different. I think that is what I like best about Sugimoto's photographs, he doesn't invent anything. He just opens himself to the experience that is right in front of him. I think that my favorite Seascape is of the North Atlantic Ocean off of Cape Breton. In this photo the sky is dark and the ocean is light, it is inversion of our normal perceptions of the ocean. I wonder if the photograph was taken at night, perhaps under full moon, becomes the ocean becomes a wonderful reflection of a heavenly light. The ideas build up from one Seascape to the next, so that the more that are on display at one time, the richer the experience. Some of them are quiet, others are bold. In some of the Seascapes the horizon line dissolves completely and the sea and the sky begin to blend together, but each of them have their own voice. Finding uniqueness and individuality within something that is standardized is a quality that Sugimoto fully developed in his Sea of Buddha series.

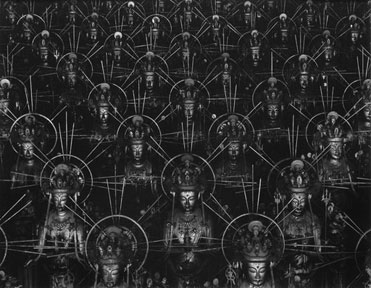

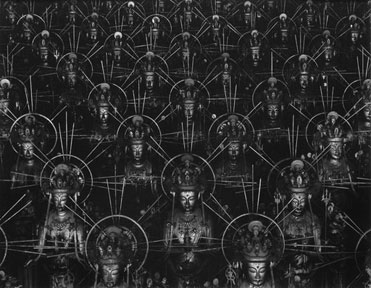

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Sea of Buddha 1995

The Sea of Buddha takes the idea of finding individuality within a uniform field to a new level. The photos are of each of the bays of the Sanjusangendo, or the Hall of a Thirty Three Bays, in Kyoto. Each of the bays is more or less identical, and are each filled with four rows of Buddhas. Like the seascapes, because the compositions of the photographs are nearly identical, the subtle differences between the statues stand out. Maybe it is a place where the gold leaf has fallen off, or perhaps it is slightly different expression, but the photograph of each bay unique and each statue has its own character. In front of the statues is a shoji screen, that fills the temple with a soft warm light but he is a master photographer, the light seems to emanate from within the statues rather than from an outside source. When I look at the his Sea of Buddha series I am reminded of Chapter 42 from Lao Tzu's Tao Te Ching:

The Tao begets the One,

The One begets the two,

The two begets the three and

The three begets the ten thousand things.

All things are backed by the shade,

Faced by the light,

And harmonized by the immaterial breath.

Even though Lao Tzu is a Taoist and Sanjusangendo is a Buddhist Temple, I think there is a lot of resonance between the two. There are 1001 statues of the Buddha in the hall and in the photographs the Buddhas seem to spread to eternity, which I think is the point of the temple and the photographs. There is some careful editing by Sugimoto in these photographs. In the temple, there are guardian spirits that sit in front of the rows of Buddhas and there is a large Buddha at the center of the hall. I think that both were eliminated to simply the composition of the photographs and perhaps create a more meditative approach to viewing the series. I know that Sugimoto has explored Buddhist ideas in other work as well. Buddhist's believe that Buddha is literally everywhere. In you and me, in the corner, under the table. Everywhere. It is the quality of literally being surrounded by Buddha, each of them the same, each of them different, that I found so compelling about the photographs. If you are everywhere, you are in an eternal state, so there is no variety, and it is in the repetition of the bays that makes the other worldly experience come across so clearly in his photographs.

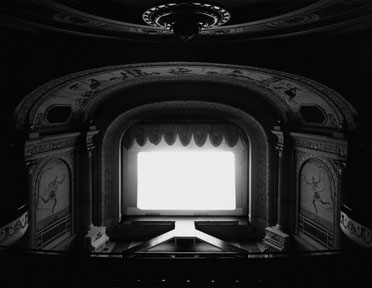

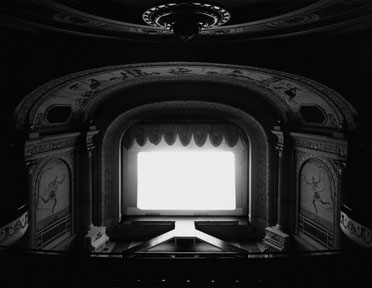

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Avalon Theater, Catalina 1995

Since the late seventies, Sugimoto has been setting up his camera in empty movie theaters, to expose one piece of film to the light of the projector for the length or an entire movie. The result is that we see a beautiful white glow, where they might have once been characters and scenes from a movie. They are all washed away and we are left with a supernatural light. Some of the photos are from inside a movie theatre, in which case the seats and the architecture are lit by the reflected glow of the screen. The soft light brings out the unique characteristics of the architecture in the same that traveling around the world to photograph the ocean brought out the unique characteristics of the place. Some of the movie theaters are drive-ins, and we are treated to the artifacts of planes flying by and other things that must have occurred at some point while the movie was playing. Each theater is special and since entertainment is changing so quickly, the photos begin to have the look of an artifact from a different time. Most of the drive-ins that he photographed probably do not even exist any more. It is only the projected light, which is the essential part of the movie experience that remains.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, World Trade Center 1996

After his experience with the movie theaters, Sugimoto began to wonder what the modern buildings of today will look like in the future, as ruins. With these pictures I think his work comes full circle. In a sense, we become the subject matter for dioramas in the future. He felt that the best way to do this was by softening the focus so that he removes the specific characteristics out of the building and the buildings reads as forms immersed in shadow. Like all of his photographs only the essential remains. We are left with buildings that seem familiar but are also eerily distant. Of course, in some of the photographs, the buildings have their own history as with his picture of the World Trade Center.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Church of Light 1997

My favorite one is the photo of Tadao Ando's Church of the Light. The light seems to be literally dissolving the concrete in the same way that the sky dissolved the line of the horizon in the Seascapes. Sugimoto shows us that the light is eternal and the building is just its frame.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Mathematical Form: Surface Model 0006 2006

Since 2004 he has been working on photographing plaster models of mathematical formulae. The models are of course very beautiful, but what I think attracted Sugimoto was that mathematical formulae are as close as we can get to an experience of permanence. I wonder if he thinks that that even if cities rise and fall, mathematics because it so fundamental to nature will still exist. The plaster models from the University of Tokyo help mathematicians and students to visualize the results of a mathematical equation. When we look at his photographs, we experience these models not as mathematical formula but as a plaster sculpture. We can see in the grain of the plaster the effects and methods of human hands to create a perfect shape. In his perfectly lit photographs, Sugimoto seems to relish these marks, these fingerprints on eternity, maybe because there is no way to escape our own humanity. The plaster models of mathematical formula become like the animals in diorama, just another aspect of nature.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Cabot Street Cinema, Massachusetts 1978

It is difficult to explain why Sugimoto's work is different than most photographers. I think the difference is that he leaves more space for the viewer. One of the things that I struck me when I was walking through the show at the De Young was that when I look at Sugimoto's wide range of work, he is somehow always reaching for the eternal in an inherently temporal medium. In the photographs of the oceans, we never see any ships or people. There is never any sign of life. Maybe because life always goes away eventually and he looking for something that won't dissolve or die. In his photographs he is looking for something he can hold on to, something that will always be there, maybe even in a million years. I think that is why most of the theatres are empty and lit only by the glowing light of the movie screen. Movie theatres are about the projection of light to tell stories and the people and the movies may come and go but the light remains constant. His photographs reveal an essential quality of a movie theatre even if the experience is not captured in the same way in our brains as on a photographic negative.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Self Portrait

He is able to get himself out of the photograph: straight forward composition, straight forward lighting, straight forward subject matter. By taking himself out of the picture, we are able to experience the vista of the ocean as if we were standing on the cliff next him. In The Sea of Buddha series, it is like walking down the long hall of Sanjusangendo with him looking at the way the statues are always the same, and always different. Of course, by taking himself out of the picture the photographs go on to reveal maybe more of himself than he expected.