|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

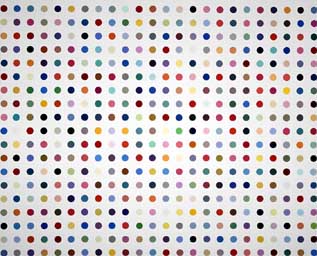

Death Staring Back You: Damien Hirst at PAM by Arcy Douglass  Damien Hirst,Chlorprotamide 1996. Household gloss paint on canvas, The Broad Art Foundation, Santa Monica. Hirst has become famous over the last twenty years for art that pushes back at the viewer, and this exhibition is no exception. His most famous works like The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, a large shark floating in a giant tank, forces spectators to confront their own mortality. The four works included in the exhibition from the Broad Collection are a good overview of some of the themes that run through Hirst's work, all presented with the fun and horrors of a haunted house at a traveling carnival. His work is at the crossroads of many contradictory ideas by being both funny and sad, shallow and deep, slapstick and profound. The exhibition includes a large dot painting from 1996, Chlorprotamide, which is composed of a series of isolated, lonely circles that radiate a generic happiness because they are all filled in with different colors. This is a great piece to start the exhibition because it explicitly lays out some of the techniques Hirst uses to generate an effect. The first is serial repetition in which an element, with or without a slight variation, is multiplied over and over until it generates a critical mass that can create a reaction. The second is the idea of an enclosure. The enclosure is a bounding area, whether it is the edge of a canvas, cabinet or a glass vitrine, that controls and concentrates the emotional potential of certain isolated elements to heighten the emotional effect. In the case of the dot painting, the dots are a serial element that is bound by the frame, which provides an order that allows the colors to be individually absorbed and apprehended by the viewer. As you will see, variations on these ideas run through the rest of the works as well. While the overall effect of the dot painting is generically pleasing, it is very difficult to get a hold of the painting because the circles never give the viewer any thing to hold on to - they are always slipping away. As the name of the painting, Chlorprotamide, suggests, maybe that is the point. The second piece, Something Solid Beneath the Surface of All Things from 2004, contains about 25 skeletons of large and small animals in two parallel glass vitrines that form a sort of ark of the apocalypse. The animals range anywhere from a dog, to several birds, a turtle, and my two favorites are the bat and the snake. They are definitely something that you would see at a natural history museum rather than at an art museum, so what are they doing here? In a natural history museum, we might be led to look at the sheer beauty of the skeletons, the interesting shapes of the bones, or the way that the bones subtly change from one animal to the next. In an art museum, I think the emphasis shifts to the realization that these animals were once alive and that these bones are all that are left behind. In Hirst's piece, we are then faced with not one death, but many deaths all concentrated in this vitrine. This is a sad piece for me because it is hard not think about what the animals were like when they were alive, and whether or not it is strange to be looking at so many skeletons when we are surrounded by so many environmental catastrophes. But Hirst is a smart guy, and most bones in a museum are plaster casts rather than the actual bones from a living animal, so you are never sure if he is just pulling your leg. But it leaves the question of how do we deal with death.  No Art; No Letters; No Society (Detail), 2006. Glass formica cabinets with medical packaging and human skulls, The Broad Art Foundation, Santa Monica. As if on cue, the curators arranged the exhibit so in the next piece you move from confronting the death of animals to confronting the death of humans, our own demise. In No Art; No Letters; No Society from 2006, there are three medicine cabinets filled with boxes of medical supplies, broken mirrors, scalpels, syringes, and in each vitrine a human skull (fake?) that is sort of a complicated play on the three monkeys: see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil. The evil in this piece is of course death that, as society and human beings, we never really like to talk about. We often act as though we are going to live forever. I forgot to mention that there are crucifixes wrapped around the handles to each of the cabinets, as if Hirst is rhetorically asking us if religion is powerful enough to hold back all of these primal fears and instincts about our own death. In this piece I began to be reminded of Hirst's strength as an artist. Not because there is anything particularly interesting in the cabinet, which is a bit heavy-handed and over the top, but because in practically every other piece in the museum we sink into it looking for comfort, visual pleasure or knowledge. In the cabinets, he becomes like death, we can't escape him. He is always forcing us to examine ourselves and our fears. Every time we try to sink into his work, he pushes back at us twice as hard saying, "Don't look me, look at you. Death is coming for you and you better learn to deal with it." It is supremely ironic that there is a very good show of Egyptian artifacts at the museum in the "Quest for Immortality" because I think that is exactly what Hirst, with a laugh and a smile, is accusing us of doing. We are living our lives like death will never catch up with us. Of course, the Egyptians sought immortality through death, and we would like immortality before death. Hirst's cabinet is full of boxes and boxes of medical supplies and different assorted surgical implements, as if to remind us of the silly ways we try to outlast the inevitable. It is here that I think the serial repetition and the enclosures are successful because by filling each cabinet to the brim, rather than strengthen us, he only reminds us of our weakness and vulnerability. He reminds us of the futility of our struggle.  Autopsy with Sliced Human Brain, 2004. Oil on canvas, The Broad Art Foundation, Santa Monica. The last piece, Autopsy with a Human Brain from 2004, is a quasi-photorealist painting of slices of a brain being poked and prodded by a pair of hands. This is from a series of paintings in which the images were taken from the mass media like newspapers, magazines or television. The slices of the brain are arrayed in a grid not unlike the series of circles in the dot painting at the beginning of the exhibition, except it is our brain and not abstract circles that fill the surface of the canvas. We never see anything of the medical technician who is examining these slices. The technician is wearing gloves and looks fairly competent, so we know this in not the result of some sort of car accident. We can't tell if the technician enjoys the work, is horrified, or by examining these slices, might be serving a larger purpose such as finding a cure for some horrible disease like cancer. We just don't know, and since we can't see anything other than the hands of this technician, it is very difficult to identify with anything other than the slices of brain on the table. What is this technician looking for by probing these slices? Our emotions? Our memories? Our thoughts? We don't know, but we can see that the slices in front of this person are nothing like our experience as human beings. We undergo a sort of miraculous transformation in this painting by being forced to imagine that it could be our brain sliced open on the table, but then we are immediately set free because the slices tell us nothing about what it is like to be human. Not be too metaphysical, but by examining the skeletons of animals, human skulls or slices of our brains, he shows that we are more than just our physical bodies. Hirst seems to be saying that we are able to transcend the death of our physical bodies, not with a battery of medical supplies and drugs, but with the simple recognition that we are more than the bodies we inhabit. Arcy Douglass is: a recovering architect, Portland artist and PORT's newest critic Posted by Arcy Douglass on February 23, 2007 at 10:52 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |