Before taking in Glitter and Doom: German Portraits from the 1920s, I visited another of the Metropolitan Museum of Art's current special exhibitions, Americans in Paris.

John Singer Sargent

The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, 1882

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

There, among the paintings of elegant Parisians lounging and strolling, I found the four melancholy daughters of Edward Darley Boit. John Singer Sargent's fluid brushwork transforms the sisters' simple white aprons into dazzling confections, at the same time revealing the vulnerability underlying their awkward poses. There are few other paintings so touched with darkness and anxiety in Americans in Paris. Americans found Paris shimmering and painted it that way, with sunlight bouncing off silk dresses and rippling water at every turn.

The two special exhibitions are appropriately situated; upon leaving Americans in Paris, visitors must descend the Met's great staircase in order to enter the hellish Glitter and Doom. Whores, cripples, profiteers and junkies populate this dismal world. Grey-skinned and dead-eyed, they look like zombified versions of the bon vivants of Americans in Paris.

During the Weimar Era, the interwar period between 1919 and 1933, Germany filled with the living half-dead. Many soldiers returned from war scarred, crippled and missing limbs. Many men were unreparable, and their widows were left to fend for themselves and their children. For some war widows, prostitution--and the emotional numbness that made that profession bearable--was the only option.

Otto Dix

The Salon I, 1921

Kunstmuseum Stuttgart

As World War I ended, Germany underwent a revolution. The German monarchy was stripped of its power, which was transferred to the Parliament. The new democratic government faced myriad difficulties, among them the heavy war reparations demanded by the victorious Allied Powers. The German government attempted to handle this debt by simply printing more money, an ill-considered strategy which soon resulted in hyperinflation. In 1920, a loaf of bread cost 2 Deutschmarks. By June of 1923, a loaf of bread cost 430,000,000,000 Deutschmarks.

While it may have looked like hell, Weimar Era Germany was more akin to purgatory. Freed of a monarchy, the country was in the process of reinventing itself. Obscenity laws were lifted, resulting in unprecedented freedom of expression. But the optimism inspired by this new freedom was undercut by the horrors of war and a chaotic economy. It was under these dire circumstances that Adolph Hitler eventually rose to power, offering a "final solution." Hitler sought to purge Germany of the "degenerate art" created by the major figures in Glitter and Doom as well as the bold formal designs of the contemporary Bauhaus movement and modernist artwork of any stripe.

It's not hard to see why Hitler felt threatened by Verism, the movement to which the Glitter and Doom artists belonged. The more experimental branch of a movement referred to as Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity--literally, "new dispassion"),Verism was the antithesis of the sterile, morally straightforward world imagined by the Nazis. Rawly expressionistic and antiauthoritarian, Verist artists frequently depicted their sitters as "types," representatives of the German social landscape.

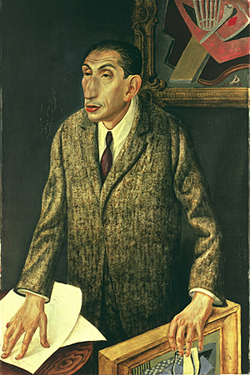

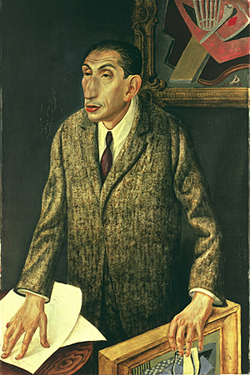

Otto Dix

The Art Dealer Alfred Flechtheim, 1926

Neue Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Preußischer Kulturbesitz

Perhaps Hitler could have found something to like in Otto Dix's depiction of the Jewish art dealer Alfred Flechtheim, an uncommissioned portrait that reduces this sophisticated art lover to a dull, petty hawker of goods. Dix had a personal beef with Flechtheim and the portrait seems to have been inspired entirely by spite. Dix wasn't anti-Semitic; he had many Jewish friends, whom he painted with equal savagery. Dix destroyed the good looks of everyone he painted, excepting himself and his wife.

After enthusiastically signing up at the age of 23, Dix went on to spend more time in the War than any of the other prominent Verists. His art is rawer and sharper than the work of most of his contemporaries, several of whom suffered nervous breakdowns on the front or avoided the war altogether. Dix's brilliance lay in his ability to crystallize and channel his rage into hallucinatory yet blunt paintings that seethe with compromised life. The quintessential Verist, Dix has far more works in Glitter and Doom than any other artist, and his vision sets the tone for the exhibition.

Glitter and Doom contains a large, well-chosen selection of drawings by major figures of Verism, which offer multiple revelations about each of these artists. The Dream of the Sadist I is a scene of gleeful mutilation that pushes Dix's horrific paradigm to a new level. On the other end of the spectrum, his beautiful Head of a Girl is startling for its calm delicacy, so unlike anything else in Dix's oeuvre.

Dix's dystopia-dwellers bear a close relationship to the the figures painted by George Grosz. Both painters portrayed archetypes with distorted features in works with a sinister tone. The condensed depth of field and collage-like compositions used by both men point to the influence of Cubist space and Dada incongruity.

George Grosz

Gray Day, 1921

Neue Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

While Grosz and Dix shared extremely passionate temperaments, their ideologies were quite different. Dix believed that all of life was guided by a creative/destructive cyclical force. He sought intense experience of all kinds and the brutality of his images came primarily out of a simple desire to capture life honestly. Grosz was an extremely idealistic and critical man who, even before the war, had been planning to complete a three volume book on the ugliness of Germans. His multi-figure compositions in Glitter and Doom were made during a period in which Grosz strongly identified with Communist ideals, and they were made as explicitly political statements. Later, a trip to Communist Russia left Grosz disillusioned and he turned almost entirely to landscape painting. One of the best portraits in Glitter and Doom shows the writer Max Herrmann-Neisse in a relatively straightforward painting by Grosz. This dignified portrait of his misshapen friend is a neat inversion of the Verist tendency to distort and savage subjects.

George Grosz

The Writer Max Herrmann-Neisse, 1925

Städtische Kunsthalle, Mannheim

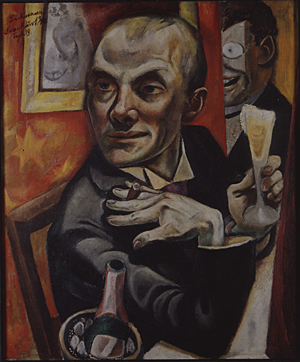

Max Beckman's featured paintings of women are beautiful, calm and formally rigorous in a way that seems slightly out of place in this exhibition. His painted self-portraits are another story; I rate them among the best created by any artist, ever and was disappointed to find only two in Glitter and Doom. Beckmann also created large multi-panel paintings of the horrors of war that are among the most impressive works from the 1920s. While these works are not "portraiture" they share a closer relationship to many of Grosz's included paintings than the Beckmann portraits that were chosen for Glitter and Doom. The Verists did such a thorough job of complicating the very idea of "portraiture" that the theme of "German portraits in the 1920s" must have presented a wide range of curatorial dilemmas.

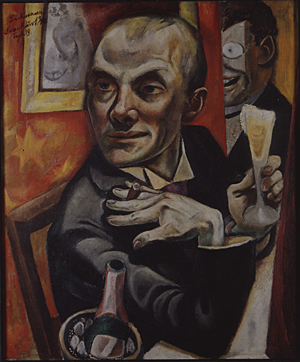

Max Beckmann

Self-Portrait with Champagne Glass, 1919

Private collection, courtesy W. Wittrock, Berlin

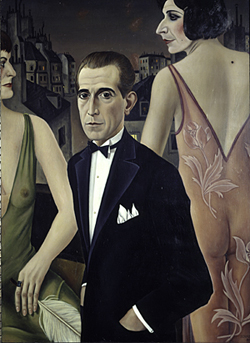

Christian Schad, who sat out the war in Switzerland, comes closest to literally living up to the idea of objectivity and dispassion implied by the Neue Sachlichkeit name. His smooth, weary creatures seem to exist perpetually in the waning hours of a strange party. Schad was enamored with Renaissance masters, and his work shows traces of the influence of Raphael.

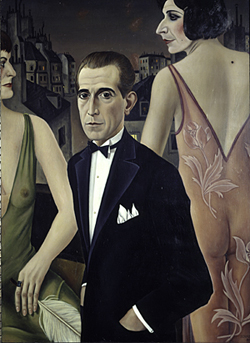

Christian Schad

Count St. Genois d'Anneaucourt, 1927

Centre Georges Pompidou, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris

These four artists are the most prominent in Glitter and Doom, which also features work by Karl Hubbuch, Rudolph Schlichter, Ludwig Meidner and several others. While a few of the omissions and inclusions are questionable, the exhibition as a whole does a thorough job of shedding light on one of the most fascinating cultural moments in recent history.

"Glitter and Doom" is one of the most powerful shows I've seen. As the title implies, it delves into a realm of conflicting emotions. I think summing it up as a show that sheds light on a "fascinating cultural moment" does not do justice to the sheer impact & universality it contains. These are not dead, dusty paintings; these are paintings that reach out and viscerally grab you.

On a more intellectual level, I was quite struck by the relationship between Grosz and his subjects... as the placards explained, his patrons were very supportive of his efforts to the point of sitting for what they knew were going to be very unflattering/disturbing portraits.

![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.portlandart.net/nav-commenters.gif)