|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

Pierre Huyghe at Portland Art Museum

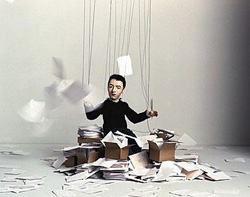

Plagued by his struggles to create a piece under the bureaucratic auspices of a commission, Huyghe fashions a duel narrative that interweaves the story of the work's creation with the story of Le Corbusier's experiences designing the building. The film is at once narrative and dreamlike, portraying the inception of both projects, the creative process of both artist and architect, their struggles in realizing their projects, and the outcomes. Le Corbusier is portrayed both as the sympathetic subject of the puppet show and as an omnipresent, though at times oppressive, source of creative inspiration for Huyghe. Throughout the narrative looms the figure of Mr. Harvard, dean of deans, an ominous insect-like black presence that embodies the burden of tradition and history that taints the commissioners of both projects as well as Le Corbusier and Huyghe. Called upon to create a piece about the Center, Huyghe responds by subverting the mythology of Le Corbusier and Harvard, creating a narrative puppet show about the struggles inherent in the creative process. In Huyghe's hands, the celebrated building by Le Corbusier is less a beacon of Modern ideals then a symbol of incomplete gestures and unrealized ideas. The Carpenter Center for the Arts was conceived in the mid 1950s as an architectural project that would reflect the utopian vision of synthèse des arts. The fusion of art and architecture is further enforced by the film's soundtrack, most of which is excerpted from works by French composer Edgard Varèse and Greek composer and architect Iannis Xennakis. Varèse's Poème électronique – an early sound-based installation played through over 400 speakers – was composed for the Philipps pavilion at the 1958 World Fair, designed by Xennakis under the direction of Le Corbusier. In early plans for the Carpenter Center, Le Corbusier included auditory and temporal elements, reminiscent of the cross-disciplinary nature of the Philipps pavilion, that were never realized. Throughout the film, Huyghe references the architect's original plans for the building, which included electronic bells that would regularly broadcast from the building, as well as his idea that seeds dropped by birds flying overhead would eventually cause greenery to sprout, embellishing the concrete surfaces of the building with organic growth. Huyghe also relays the story of Le Corbusier's compromise to the design of the building itself, which underwent many modifications in order to fulfill the expectations of its commissioners. In one scene, Le Corbusier is depicted in heated negotiation with Mr. Harvard over the Center's design, as the building transmogrifies before their eyes. Huyghe's film consistently returns to the notion of artistic compromise, and in doing so, hints at the failure of Modern idealism. This is Not a Time for Dreaming is not the first work by Huyghe to reference Le Corbusier. Huyghe's Les Grands Ensembles (1994–2001) casts two high rise postwar apartment buildings – inadequate imitations of Le Corbusier's social architecture – as the film's main characters. Their spectral volumes communicate silently through flickering lights, a strangely poetic musing on Modern alienation and the failure of progressive thought to result in viable urban programs. Through the retelling of the story of Le Corbusier's Carpenter Center, Huyghe gives voice to the architect's unrealized visions for the building. By devising a puppet play – a mode of entertainment and an enclosed narrative form – and constructing a temporary stage, Huyghe creates a physical and conceptual place for these ideas to be re-enacted. Huyghe's singular vision dominates the narrative, a nod to the singularity of Modernism. At the same time, he undermines his own power as storyteller. Huyghe relies on metafictive devices, telling a story within a story about the creation of his own piece. One is never left unaware of the mechanics of storytelling. The strings of the marionettes are clearly visible and the camera's point of view changes arbitrarily throughout the course of the film, at times revealing the sides of the stage, the walls of the theater and silhouettes of the audience members' heads. The final scene, "Epilogue as prologue," is a dense monologue by Liam Gillick – the British artist who uses architectural forms and theory as an integral part of his work – as read by a bearded Harvard professor. Here, Huyghe completes the circularity of his narrative, ending the film precisely at the moment that the play (and thus the film) begins. It is the only part of the film that employs words, providing a statement that is at once a practical introduction to the characters, a disclaimer about the subjective nature of such a project, and a self-contained critical text about the film of which it is a part of. Despite the self-conscious, hyper-aware nature of Huyghe's piece, he does not completely disavow the artistic process. While the creative process is shown in a parasitic relationship to the institutions that support it – much like the relationship of Huyghe's temporary stage to the Carpenter Center, or Huyghe's project to Le Corbusier's legacy – it is not depicted as an entirely futile exercise. The play may be, as the epilogue explains, "A set of relations with no dialog. A communication by proxy." But in the end, relations are made, buildings are constructed, commissions are completed. In the fourth act of the play, Le Corbusier is shown shortly after a dream sequence in which skeletal models of the architect's previous buildings float dreamlike above his head, providing creative inspiration for the first sketch of the Carpenter Center. The film cuts to an extended scene of the bespectacled architect performing a soft shoe routine to "Le temps des cerises," performed by Charles Trenet, the French Frank Sinatra. The song – a nostalgic and bittersweet love song written in the 19th century by Jean Baptiste Clément just before the Commune de Paris that would later become a song of resistance during WWII – is about the time of cherries, the point between spring and summer and a signal of change. In Huyghe's film, it evokes the time of creative inspiration, a moment of fertile artistic and conceptual indulgence before an idea's realization in the physical world. Posted by Katherine Bovee on December 18, 2006 at 13:19 | Comments (1) Comments Katherine, Just for the sake of breaking out an old saw, Ive always rejected the idea that modernism was about only about progress. Picasso's Les Demoiselles was clearly an anxious painting about change and unresolved context. Same with Mattisse's Red studio. Same goes for Pollock's classic works or even Leger menacing plastic constructions. But yeah, to sell modernism to an American audience Alfred Barr defined a much narrower and more digestable model that looked a lot like "progress". (I loved it earlier this year when Elderfield displayed a diagram called the torpedo at PAM.) Barr's legacy is part of the reason MoMA has such an identity crisis these days (maybe they need to comission Huyghe to do something?). Huyghe seems to have refined Matthew Barney's pagentry, marrried it to wonder, logistics and bureaucracy and created a wonderfully reflexive and nearly upbeat body of work. It's the French version of optimism so to many Americans it might seem pessimistic. It's interesting because European reviews of his shows (particularly the Tate show) note the optimism and Americans focus on the pessimism. Posted by: Double J Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |

![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.portlandart.net/nav-commenters.gif)