|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

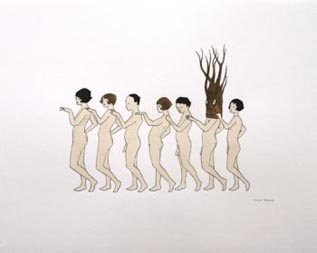

Election day thoughts on drawing in the aughts

Posted by Jessica Bromer on November 07, 2006 at 12:18 | Comments (4) Comments I love Dzama and Pettibon, can't stand the clones. The clones affectation of self-consciousness simply isnt enough to legitimize this glut... although it does make nice cover art for the Stranger/Mercury. Interesting how Dzama's aesthetic was the elephant in the room at the 2002 Whitney Biennial. The Canadianification of the art world... eventhough I don't dig a lot of this work the Royal Art Lodge deserves a lot of respect. If you were buying Dazma's from Liz Leach and Greg Kucera 6 years ago you might have made a pretty good choice.

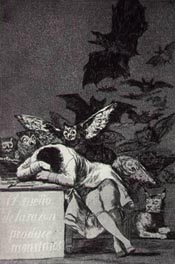

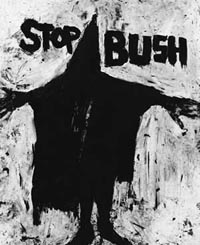

Posted by: Double J The Royal Art Lodge and their collective shows deserve the initial kudos for bringing Dzamaisti (ha!) to the world. There is a fine line between illustrative work that "works" like Dzama's (who I love, but simultaneously am tired of, and yet want to see more), and "smacks of cliched gag/idealism" illustrative works with angry young man messages that seem to be everywhere. Chris Ware (and Marjane Satrapi) are like a breath of fresh air when confronted with those, but for whatever reason the art and comic world haven't quite crossed over that sequential static boundary, is there something scary to the artworld about mass consumable graphic novels? Hmm.,. "The work of the hand is being used less frequently in popular advertising, so the old distinction between "mechanical" handwork and "artistic" handwork has largely been replaced by a distinction between digital work and handwork, period." I would like to see you expand on this thought, because i'm not at all sure I agree with this statement. A lot of digital work starts out as handwork, what's the boundary? It's being used less, I agree, but it's popularity comes and goes in waves. And finally, speaking of "explicitely communicative" politically motivated artwork - talk about an "ever-more-soulless popular culture"... has popular culture become so brain-damaged that we can only respond to angry didacticism? Posted by: squidtronic I see the Serra not as angry didacticism, but as an attempt to channel the experience of victimhood through a crudeness that speaks of desperation--a plea rather than a command. His raw form reworks the degredation of being made anonymous into an expression of the universal experience of suffering. It commands empathy more than obedience... I've seen less artistic renderings of this figure that reduce it to an icon, a symbol onto which the viewer can project political philosopy. Serra gets to the heart of the matter. I say it's art, not just propaganda (while acknowledging that anyone arguing the opposite has a lot of ammo). As for digital/hand issue...maybe I'll have time to tackle that tomorrow. Any pro designers/illustrators want to weigh in? Posted by: Jessica Bromer Squid T., I tried to couch that idea in a lot of "less" and "largely" but perhaps I should also have said "is being replaced" or "looks as though it is going to be replaced." The parts of this essay where I attempt to make sense of the zeitgeist are definitely the most conjectural. Essentially, wherever you find a sweeping artistic trend, there often emerges a pattern: A promoter, a star, and an underlying cultural restlessness. For example: Critic John Ruskin + Charismatic artist/ringleader William Morris + (The Industrial Revolution x widespread dissatisfaction with "alienated labor" and shoddy goods x craftspeople no longer needing to supply a huge demand and therefore specializing and experimenting leading their work to become more idiosyncratic and thus recognizably artistic) + the notion of a utopic community as the defining ideal of the age = The Arts and Crafts Movement So with Quaint Drawing there's ((Gallerists David Zwirner + Richard Heller--the Royal Art Lodge deserves respect and some credit (roughly akin to the importance of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood to the above example) but they might well have remained in semi-obscurity had their crew not included the brilliant Dzama)) + Dzama and his prodigious talent/prodigious output + a healthy market for mid-priced work and a broader customer base thanks to the popularization of the art fair x (y) = Quaint Drawing Craze. So what is (y)? It seems like more and more of what surrounds us (not around Portland, but more or less anywhere directly adjacent to a highway or in any supermarket without an organic section) appears to have originated somewhere in Adobe Creative Suite, rather than at a table with foamcore, pencils, paste, exacto knives, etc. Clients in search of high-end design can afford to take the gambit of paying a designer well enough that he/she can take the time to experiment, draw, build, etc. in order to come up with something fresh and idiosyncratic. The larger pool of low-end designers have to watch the clock more carefully, and working on a computer is more efficient, as is copying someone else's example. At this point it's not difficult to make something on a computer that, when reproduced, looks like it could have been drawn by hand. Whereas not so long ago, "by hand" was the only way to make much of what is now created using computers. Coincidentally (or not???) in art we've begun to see a lot of drawing and surreal model-making with foam, tacks, etc. Trends do come and go, but this technology is so young and so fast-moving that it's hard to know how different design will look after the computer is a historically established creative tool. The skill of drawing as part of a standard upper-class education, popular pastime, and widely used means of recording the appearance of things is long past, and even the time when it was standard for art schools to turn out graduating classes of proficient draftsmen has passed. Before photography, newspapers would send sketch artists to the scenes of crimes and fires. The degree of skill required for that very practical position is now the province of a select few and that rarity may be the last step to breaking down the barrier between graphic depiction and art. Even though there are still, and always will be, illustrators who primarily create work by free-hand drawing, there are fewer people employed in purely practical drawing. Where the makers of a medical dictionary may have once employed a medical illustrator to draw an organ, they now at least have the option of creating a computer rendering, possibly choosing to do so in order to offer students a more layered image. Or, makers of bottles of lavender--scented shampoo might have at one time employed an illustrator to draw a lavender plant, but, because computers are available and have a buffet of available treatments for abstract form, now choose an abstract lavender-colored graphic instead. Art objects are monetarily valued for their aura of uniqueness (Larger print editions of equal "artistic quality" to smaller editions by the same artist being valued at a lower price per print, for example). Additionally, uselessness as anything other than art is what allows the possibility of vast fluctuations in a work's monetary value. Whereas drawing, as a service for which one can be paid, has long had a value in a practical, competitive marketplace. So the fact that fewer and fewer people use drawing by hand as a practical tool may be one of the reasons that drawing is being accepted as commensurate with painting, sculpture, the act of crawling naked through broken glass, i.e major work, rather than preparatory or minor work. By having less practical value, drawing is freer to accumulate "art value." Illustration and art will probably always have an awkward, convoluted relationship, as will art and craft, art and design, art and entertainment, art and the public, art and theory, art and criticism, art and artists, etc. but there has been a subtle shift in the balance of power over the last few years, and my best guess is that it has a little bit to do with CAD and Illustrator. Posted by: Jessica Bromer Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |

![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.portlandart.net/nav-commenters.gif)