|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

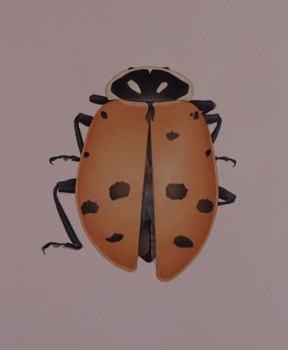

Artists and Specimens at Lewis and Clark College  Cornelia Hesse-Honegger Lady Bird Beetle from Richland, Washington (1998) Be sure to make the trek up Palatine Hill to see the Artists and Specimens show at the the Hoffman Gallery; it will give historical documentation, classification, and our beloved pioneers new identity. This show is one of savvy mimicry and rich, kaleidoscopical commentary. It is funny and profound and makes you think twice about Audubon and Lewis and Clark and even Ranger Rick. All of a sudden these rather dry dead dudes perhaps maintain intense fetishes, insane biases, and inane conclusions. The act of research becomes commentary/editorial/, and the notions of truth, language, and logic are suspect. This is an exhibition that disrupts our rooted ideals of the things we accept without question, i.e. myth and science, and illustrates that while in definition they are opposite, in reality they are forever inconspicuously overlapping. Sue Johnson's anatomical renderings of Pegasus and Peter Cottontail are quite the example. Johnson's renderings are blatant, simple, and surprisingly devastating: magic's intestinal tract and colon in rendered detail, in front of our eyes, and on the wall. Even as an adult, I could not wrap my mind around it. And in an opposite kind of way, Johnson recreates the experience of first time viewing of so much of what was discovered and how the findings must have shattered what was popular belief. In essence, Johnson's drawings recreate the context of history without anything historical and thus create an experience which we cannot seem to imagine. Howard Zinn and Milan Kundera would be proud.  Installation view, work by Mark Dion (fg) The documentation of asymmetrical insects by Cornelia Hesse-Honegger is a subversive protest and cautionary foreshadowing against the effects of radiation. The precision and subtlety in her hand makes her warning all the more strident as we project our own bodies onto the thick paper. Deformed antennae and uneven demarcations become missing ears and mottled digits as Hesse-Honegger's prophetic work hits home. There are politics in entomology and philosophical ruminations on truth in Mark Dion's glass display cases. Dion makes the lives and subsequent work of explorers themselves subjects, giving material to the rest of the exhibitions already audible hints. His cases become the artifacts of the ghosts that already hover and loom in the gallery space. Barton Lidice Benes' pieces give soul and character to what in contemporary society some might easily confuse with insignificance, or even trash. In a society which abounds in endless amounts of stuff, these tiny eccentric objects, (Norman Mailer's backwash, Bjork's potato chip, etc.) are still too young to gauge the extent of their potential future historical significance. It is Benes' act of labeling and arranging them, in essence his sheer attention to them, which makes them important. In a much more traditional sense, it is the same with Tony Foster's work; the act of his watercolor documentations of endangered places (in lieu of a more contemporary act of photography) is the statement of importance and attention and the message that this is not something to be taken for granted. These artists' documentation of what they note as contemporary experience is an infinitely interesting exhibition. The viewer walks through the show with thoughts that may range from Lewis and Clark to Liberace, yet the true specimen of this exhibition is the documentation of the behavior of the strangest species, humanity. Our unending and insatiable desire to know and understand the complexities of our surroundings is unique unto ourselves. The subsequent attempt at capturing and documenting (and often butchering) nature's intended poetry unconsciously becomes our own endearing, idiosyncratic commentary upon our own species and the systems we create for ourselves. The exhibition of this in Artists and Specimens leaves the viewer with countless ruminations and a sudden awareness of the beauty and profundity of man's fallibility. We leave the show seeing our grand devices and histories with fresh eyes and the notion that our contemporary ambitions might one day be our past mythologies. Through October 22nd Lewis & Clark College: Eric and Rhona Hoffman Gallery 0615 S.W. Palatine Hill Rd Portland Oregon 97219 Gallery Hours: Tuesday through Sunday, 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. Parking on campus is free on weekends.For more information: 503-768-7687 Posted by Amy Bernstein on October 12, 2006 at 21:09 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |