|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

NCECA Roundup (Part 2) While one would be hard-pressed to definitively extrapolate recent currents in ceramic art from the work included in NCECA, a broad range of work was represented, and many shows found resonance with others around town.

Over at Pacific Northwest College of Art, four Alfred University grads—Ian McMahon, Nathan Sherman, Marc DeBernardis and Robert Marzinsky—take media-based concerns to an extreme in an exhibition entitled Composite. Four large-scale works in PNCA's Swigert Commons employ ceramic in its raw form, boldly taking site-specific clay and mixed media sculptures to architectural dimensions. The most successful piece is a horizontal band of raw clay, suspended in mid-air between walls and columns to delineate a new space that interacts with the building's existing architecture. It acts as an unavoidable public sculpture within the commons space. Visitors and students are confronted with a choice to walk around the sculpture, thereby changing their normal trajectory, or enter inside of the sculpture by ducking underneath the band, which was positioned several feet off of the ground. Although it serves as an architectural feature or barrier, its impermanence is apparent, as the raw clay bears deep cracks reminiscent of salt flats, a reminder that the construction could crumble at any moment.

All works in Composite share an interest in playing between monumentality and impermanence. In one work, four speaker towers, enclosed in wooden boxes, emit low, barely perceptible bass tones. Thick slabs of raw clay are placed over the openings. One of these slabs had finally succumbed to the vibrations of the sound, laying in a slumped heap at the base of the tower. In another work, several crudely constructed platforms hold sculptural work that resemble skeletal architectural models. Each platform is mounted on wheels, making the platforms vulnerable to the possibility of movement, which would most certainly cause harm to the sculptures themselves. The fourth piece is comprised of a network of minimal architectural models spread throughout the space, linked by large metal arcs stretching two stories high. One model mimics the architectural features of a nearby stairwell, while another resembles an aerial view model of the neighborhood surrounding PNCA. Each model is placed atop improvised pedestals fashioned from slabs of raw clay, referencing geologic layers and providing a ground that became uneven as the clay dried. Discreet surveillance cameras peered down over these models, the live footage broadcast in other parts of the room, as if waiting for a natural disaster to animate the small-scale spaces. In Composite, McMahon, Sherman, DeBernardis and Marzinsky used clay as a non-static material, full of potential to enter unstable states.

In a temporary exhibition in the upper floors of Portland Art Center that came down in mid-March, University of Washington MFA student Matthew Mitros took a very different approach to material concerns, with an inventive use of firing and glazing processes. Mitros' work shares the same love of caustic color and surface that informs the impasto surfaces of Jesse Hayward. Mitros exploits the chemistry inherent in the process of firing clay and glazes, and his wall-works seem like a science experiment gone bad (in the best possible sense of badness). On 9th and Flanders, PDX and Pulliam Deffenbaugh mounted shows by two artists who exhibit regularly in Portland. PDX artist Bean Finneran and Pulliam Deffenbaugh artist Jeffry Mitchell both indulge in decorative ceramic work that goes beyond pure eye candy.

Finneran's work opposes the association of clay with earthy aesthetics, although there are plenty of natural associations to be found in her work, which evokes everything from aquatic life to grasses. Hundreds of gently curved, uniformly colored, extruded rods are assembled on-site to form organic mounds installed throughout the gallery. Colors range from minimal white to construction orange, some tips highlighted with a dab of colored or clear glaze to catch the light. Finneran's work is unabashedly decorative and playful, but the consistency of her formal relationship with her work and the uniqueness of each installation keeps the work from growing repetitive.

At Pulliam Deffenbaugh, Settle-based artist Jeffry Mitchell exhibited a new series of decorative kitsch objects that included frilly wall hangings and gloriously gaudy domestic objects like lamps, planters, pickle jars and vases. Freely mixing in references to Delft production ware and Chinese bronzes, Mitchell's oeuvre is unapologetically and disarmingly sweet, filled with dancing bears, decorative flourishes and plump elephants. However, several pieces in this new series introduce a chain linked element that clearly disrupt his flowers-and-bunnies aesthetic. The carefully controlled casualness of Mitchell's style disrupts the uniformity associated with mass-produced objects and the artist constantly plays between high and low. In several series including his Fu Dogs, Mitchell's version of the statues that flank every Chinatown gate, he covers the surface with opaque metallic glaze. The faux bronze finish revels in the idea of cheapness, while imbuing his work with a clearly handmade quality.

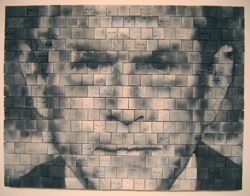

Around the corner at Elizabeth Leach, Richard Notkin presented work that was the near antithesis of Mitchell's, with his ultra-precise craftsmanship and exploration of war, politics and the dark side of human nature. The central work in the exhibition, A Precarious Moment in History, is a mural comprised of individual tiles bearing imagery of death, warfare and destruction. Together, they form a large-scale drawing depicting the face of our current president. Here, Notkin continues working in the same process of his 1999 mural of a mushroom cloud, entitled The Gift, which can be seen at the Portland Art Museum. In his latest mural, Notkin takes more risks in his choice of subject matter, placing the current political climate within the continuum of history, but artistically, the result is not quite as convincing. With its historical specificity, A Precarious Moment in History lacks the ambiguity of The Gift, in which it is uncertain whether Notkin is reflecting on the past or portending the future.

Other work in the exhibition shows Notkin in top form, with old and new teapots from several ongoing series. The cult of the teapot not only brings with it a marketable niche, but, as Notkin has previously stated, it can be considered a blank canvas for ceramists, the structural limitations encouraging formal innovation. Inspired by Yixing teapots, Notkins' teapots are minutely detailed and small in scale. His lexicon of visual elements—hearts, chains, ruins, atomic clouds, skulls, dice, oil barrels and enlarged ears—become icons for the contemporary dilemmas that 20th century politics, technology and warfare have presented us with. Particularly poignant are his series of 20th Century Solutions teapots, scale model ruins of brick buildings that speak to the physical and moral carnage that modern day warfare has left in its wake.

At Gallery 114, a group exhibition entitled Warfair confronted the same thematics. The majority of the seven artists addressed this theme with some element of humor, perhaps a hopeful sign in the face of the hopeless continuum of human conflict. Monica Van den Dool's figures resembling oversized plastic army men re-imagine soldiers engaged in more frivolous activities like playing with a dog or holding a double scoop of ice cream. Charles Krafft creates souvenirs of war, creating casts of semi-automatic guns, grenades and illegal weapons in Delft blue-and-white china. Karl McDade's crudely hewn wooden cart is filled with pots fashioned through cheap sculptural elaborations into I.S.D.s, or Improvised Sculptural Devices, parodying the feats of imagination that produced Iraq's weapons of mass destruction.

Today is the last day to view these exhibitions at PNCA, PDX, Pulliam Deffenbaugh, Elizabeth Leach and Gallery 114. [To be continued…] Posted by Katherine Bovee on April 01, 2006 at 9:38 | Comments (2) Comments All these shows were fantastic. PNCA's show was a welcomed relief, after it having consistently "not good" artwork for the last couple months beforehand. Notkin's work was beautiful. In fact, the one I thought was completely worthless in the George Bush peace. It just felt liek the piece where he was saying "oh just in case you didn't notice, this is about politics." Other than that, who knew someone could make crumbling building look so precious. Finneran's "Koosh" balls are exciting. That's about all I can say. Finneran really removes clay from the crude aesthetic one normally associates with clay. The only thing that made me sad about all the NCECA exhibitions, is that in all this clay business, no one cared about Gregg Renfrow's beautiful and intense color fields at Liz Leach. They were stunning. Great month in Portland art though. Posted by: Calvin Carl agreed, that was Renfrow's strongest show to date.... that said I think Vicky Lynn Wilson was the big winner last month (all those red sparkley eyes in a sea of white) and Daniel Barron was the big new discovery. Posted by: Double J Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |

![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.portlandart.net/nav-commenters.gif)