|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

Multiplicity (NCECA Roundup Part III)

Multiplicity could have easily gotten lost in the predictability of its format—a group show defined by a single word that serves as both title and theme, with an expansive topic that gives the curator the ability to usher in everyone from the artist du jour to heavy hitting art stars. These types of exhibitions often seem hinged on a "curatorial-lite" formula that has proliferated in tandem with the crop of curatorial studies programs that have sprouted up over the past decade. Weakening the relationship between curatorial practice and academia, such exhibitions easily fall into curatorial sloppiness. When done well, however, they can provide a dynamic alternative to strictly historic or academically-grounded exhibitions. Curators Kate Bonansinga and Vincent Burke were able to reign in the exhibition at the Portland Art Center through careful selection and adept installation, turning out one of the best offerings of NCECA's ceramic-oriented exhibitions. The exhibition was mounted in Portland Art Center's yet-to-be-renovated Chinatown space, and the scale of the work combined with solid installation gave the show coherence despite the unfinished nature of the gallery space. Bonansinga and Burke focused on large-scale sculpture created by massing smaller multiples. Thematically, it's resonant with an exhibition on view earlier this year at the Fabric Museum & Workshop in Philadelphia entitled Swarm. But, whereas Swarm took natural systems and the theory of "swarm logic" as its basis, Multiplicity looked to the factory, including work with a link to mass-production. Most work in the show employed a minimal color palate and slick, uniform surfaces that borrow heavily from early and contemporary industrial processes. Bean Finneran's piles of extruded rods occupied the center of the show, her neatly ordered stack of thin red cylinders forming a vivid focal point for the rest of the work in the show, which was dominated by more demure hues. While a show of this nature could potentially become cluttered with masses of small objects, careful attention was devoted to the relationship between individual pieces. The stacks of Finneran, which are reminiscent of grasses and aquatic life, formed a visual counterpart to the seven large semi-spherical shapes of Gregory Roberts, installed in a loosely circular arrangement on the wall. Like the work of Finneran, Roberts' The Same But Different is intended to be configured differently during each installation, subtle variations adding an element of chance. The individual shapes resemble oversize bug eyes, the center of each dark half-sphere covered by Roberts' signature honeycomb ceramic, an ultra-fine, precise grid of cells that at once attests to his fascination with natural forms and to his affinity for the mathematical order underlying these natural structures.

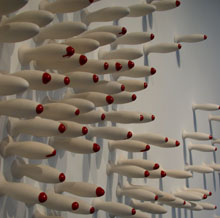

Juana Valdes and Kay Hwang also exploited the variable nature of multiples. In Hwang's Generation II, several hundred red-tipped porcelain forms protrude from the wall. The uniformity of their shape and pristine surfaces are offset by the random distribution of the forms, which are reminiscent of both biological appendages and, as Bonansinga has suggested, explosives.

Juana Valdes exhibited a fleet of small cast porcelain objects made to resemble paper boats. It's unclear whether these boats are entering or exiting, invading or escaping, attacking or meandering. The work of Valdes—who is the only artist in the show who does not work primarily within the ceramic medium—is informed by her own experience as a Cuban immigrant who moved to the US in the 70s. Her boats are small in scale and their substance implies fragility, both in their reference to the temporary nature of paper boats and the actual, breakable porcelain in which they are crafted. However, these are not precious objects—their link to cheap mass-produced souvenirs counteracts the diminutive scale and implied impermanence. The boat form was originally conceived while in residency at the .ekwc in Den Bosch, Netherlands and was part of a project that invited artists and designers to respond to the phenomena of cheap, reproducible Dutch souvenirs.

Marek Cecula and Shawn Busse also make reference to industrial objects and processes. Busse's Metronome is comprised of a series of glossy white ceramic violin forms that occupy sculptural metal cases positioned atop a row of pedestals. A bar code decal is prominently displayed on top of each violin, but the work challenges the uniformity of the mass-produced object, each object bearing subtle variations because of the techniques that Busse used to reproduce them. The work also creates a visual metaphor for patterning found in Western music. Like the work of Busse, Marek Cecula also references aural experiences in his work Interface, Set IV. The work is enigmatic and intimate, a row of five rectangular white china slabs bearing an imprint of the human ear. The work is part of a series that uses the repetition of forms from the human anatomy to create interesting negative spaces. Here, each sculpture is open in the middle, the inner chambers of each ear lined in a metallic glaze and forming a negative space that connects each sculpture. The work is precise, attesting to Cecula's accomplishments in the field of industrial ceramic design working through his studio Modus Design.

The Porcelain Curtain of Jeanne Quinn is linked to design by her use of decorative shapes that normally adorn china dinnerware, wallpaper and other domestic items. In previous work, casts of everyday objects like balloons and cotton swabs become the basis for three-dimensional arabesques and decorative lines in space. In Porcelain Curatain, Quinn uses a network of abstract, highly decorative forms linked by invisible thread to form a three-dimensional curtain that hangs before a painted Rorschach-like shadow on the wall. Although the individual elements are decorative, the shapes are bloated and slightly distorted, verging on the grotesque. Each form is left unglazed, giving them a chalky, bone-like quality that imbues the piece with Victorian eeriness. Thematically, Multiplicity gets to the heart of one thing the ceramic medium does quite well—allow for mass-reproduction of objects. In this way, the show acted as a selective sampling of work by artists who use multiplicity as a central strategy, both in the reproduction of identical or nearly identical multiples and the installation work within the gallery. As a result, the choice of creating a media-specific exhibition made sense, rather than acting like an arbitrary and artificial melding of theme with media. Posted by Katherine Bovee on April 19, 2006 at 15:39 | Comments (1) Comments It was a bit stiff but it was good to see PAC looking good in this show. The hang made good pragmatic use of the somewhat vague space by presenting the artists discreetly with Hwang's piece anchoring the exhibition. Everything else is pretty courteous and that is the overall feeling here... respect, although its the rather professional "here's my card" kind. Is there a lot of fire here, no... but the theme made that practically impossible. It will be interesting to see how PAC handles the rennovation. The carpet has got to go and I think and a good architect should work at clarifying the space's irregularities. Right now it competes with the art. The old plan of using moveable walls on tracks like Woolley's "Wonder" space is a bad idea because walls that dont meet the floor are really problematic for installation artists. Installation artists often use the solidity of the wall as a foil. Take the solidity away and the wall becomes a distraction. Those kinds of walls work best for paintings. Posted by: Double J Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |

Kay Hwang

Kay Hwang Image courtesy Juana Valdes

Image courtesy Juana Valdes Marek Cecula

Marek Cecula Jeanne Quinn

Jeanne Quinn![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.portlandart.net/nav-commenters.gif)