|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

The Sensualist: New Work by Eliza Fernand Eliza Fernand is developing an aesthetic of sensuality, focused on the primacy and temporality of bodily experience, in a new show at Rake Gallery as well as several recent performances for her Thesis at PNCA.

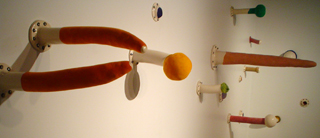

Ceramic Objects to be Touched In the stage space in the back of Rake, Fernand displays her tactile ceramic work, undeniably sexual objects budding from the back wall. Although the shapes are abstracted, they draw from the visual and sensual vocabulary of reproductive systems, both plant and animal. Tubular shapes proliferate, bringing to mind the pistils and stamens of flowers as well as human sexual references. Interestingly, mounting hardware for the pieces is constructed into the ceramics themselves. A critical component is the fact that the mounting plate is part of the formal structure of the object. These objects appear organic, but intention is built into form. Fernand intends the pieces to be mounted on the wall, and constructs the potential for interaction into the object. It is not simply an exploration of organic reproductive forms. The objects are meant to be touched. Fernand coats the ceramic protrusions with a surface of flocking, so that the hard ceramic gains the tactile quality of velvet. It is this combination of the hardness of ceramic and the softness of velvet that gives Fernand's work its overwhelming erotic charge. This erotic power residing in these objects (which beg to be touched) is a defiant attack on the accepted aura of the art object, and its surrounding taboos. Van Gogh is an undeniably tactile painter. In looking at his work, haven't you ever longed to run your hand over the surface of the painting? This kind of sensual interaction is strictly forbidden by the taboos of the art object. The art masterpiece demands separation from the viewer. It projects experience while the viewer receives. Incidentally, this is why purchasing a Van Gogh poster is essentially a futile enterprise. Posters are smooth and thin, the separation has increased to the point that the image, free of its tactile sensation is harmless and ineffectual. Great art objects are thought to transcend time as containers of specific experience, readily accessed, and undiminished by the viewer. They require receptivity on the part of the viewer, a quiet, "open" mind. The Mona Lisa contains the same experience which it re-imparts to every viewer ad infinitum, and control over that experience remains within the object itself. But sensuality always requires more than receptivity, it requires activity! And sensual experience exists as a temporal, unrepeatable event fixed only in memory. The art "masterpiece" contains an infinitely repeatable experience which assures the immortality of the object. Sensual experience is quite the opposite: events exist in a limited continuity, bounded by memory and mortality, and cannot be repeated. Sensuality is a denial of immortality. Sensual experience persists only in the memory of the participants, and cannot be recreated because each event is a new occurrence. The controlling presence of the immortal art object is absent, replaced by active interaction. Sensual experience naturally dissipates, while the art object attempts to infinitely suspend that experience. This is perhaps the best definition of beauty: the infinite suspension of sensual experience. However, sensuality is the more human ideal: life is brief, and the full experience of the senses is rich but fleeting. If people dared to touch Fernand's ceramics (which most people don't), over time they would disintegrate.

Sploog In Fernand's Sploog series, hard, spherical, ceramic objects spurt opulent fabric drips from central holes. Fernand's work has an unrestrained visual decadence. Formal concerns are secondary. Formal properties are subjugated to a greater purpose: visual and tactile sensation. Fernand's work speaks the most basic human language: that of pleasure, touch, and interaction. She chooses materials based on their ability to invoke sensual pleasure in the viewer: sequins and gold ribbon adorn the opulent fabric drips.

Tube Cloud Tube Cloud hovers menacingly / peacefully in the center of the gallery like a Rococo Man 'O War. Pink tendrils descend from the central mass and burst into fleshy, sequined tubercles. Tube Cloud is above a round cushion. When one understands the interactivity of the ceramics, it is easy to see that the artist intends the viewer to sit on the cushion amongst the pink tendrils and fleshy tubercles. The accidental motion of the sitter animates the tendrils and tubercles. One finds oneself as gently caressed as a clown fish by a sea anemone. One of the fragile tubercles has already broken. The important temporal limitations of sensual experience have naturally led the artist into performance. Fernand's performances have thus far been held in non-gallery spaces due to the specific environmental demands of each piece. Two have already occurred and there are two more planned before summer. The performances are open, feel free to contact me if you'd like to attend one.

The First Performance The performances involve similar sensual themes, focusing on the essential, bodily experience of being human. Two thus far have involved food and abstractions of sexuality. The first took place in a park on cold winter day. Fernand was dressed in a costume emulating pregnancy. She crawled around on the lawn consuming planted asparagus. Eventually the pregnancy costume revealed a long fabric tendril which she tied to a tree before exploring the forest. The imagery phased effortlessly between maternity and regressing to an infant with an umbilical cord still attached. None of the images could be distinctly separated from the larger conceptual array. The piece abstracted and conflated the universal truth of individual experience of the body, there was no easily identifiable single metaphor. Attempting to sum up the performance by saying: "that was about birth," would have been woefully inadequate. Instead, it seemed to be about the general metaphysical implications of the processes of the body. It dealt with an abstract, confused, pleasurable, and ultimately spiritual understanding (or misunderstanding) of what the body is. Fernand's project is breathtakingly simple: to approach the body as if experiencing it for the first time, as an absurd, pleasurable machine. Dissection helps us understand how it works, but the question "what is it for?" can't really be answered.

The Six-Foot Sushi Roll The second performance took place in a warehouse art loft. Upon entering the studio, the first thing we saw was a six-foot sushi roll, not yet rolled up, and a honey bear. Fernand entered the studio wearing a pink bodysuit covered with her fabric drip forms and a cartoon eye mask with the pupils looking upward ecstatically. The drip forms made a shaking sound when she danced. She danced with no music except the rhythm created by this sound until she was exhausted. Then she flipped over the eye-mask, which had "serious eyes" with pin-point pupils on the other side. She walked over to the table, squirted the honey into the sushi roll and rolled it up. Then she turned the mask over again, back to the ecstatic eyes, and climbed on top of the table to eat from one end of the six-foot sushi roll, inviting us to eat from the other. We were all afraid to break the taboo that prevented us from eating from the same long sushi roll, but eventually, one by one, we overcame that fear, and went to eat from the other end. It was truly delicious, the honey was a delightful counter-point to the wasabi. In breaking the taboo, we experienced a kind of bodily intimacy together. It was an admission of the biological continuity which we all share and never acknowledge. We all experience the pleasures, terrors, humiliations, and ecstasies of the body in the same secret way. We are all part of the continuity of biological experience. We are all eating from the same infinitely long sushi roll. Eliza Fernand • Abstracted Protrusions • Through April 1st • Rake Art Gallery • 325 NW 6th AVE • Portland, OR, 97209 • Posted by Isaac Peterson on March 27, 2006 at 1:18 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |