|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

Sophie Calle at PAM

Sophie Calle has been accused by critics (and subjects) of being a voyeur, a spy, an amateur detective, a "world class snoop" and a specialist of intrusion in the private lives of others. Calle's work originates in aspects of performance or experience, oftentimes autobiographical in nature and involving the lives of strangers. Since the 80s, the French artist has embarked on projects that include covertly following an acquaintance that she met once at a party in Paris—where Calle lives and works—to his vacation in Venice; dutifully recording the contents of strangers' hotel rooms while posing as a chambermaid; and documenting stolen paintings through photographs of the empty voids left behind along with transcriptions of interviews with guards and curators who worked in close proximity to these masterpieces. Although Calle's work emerges from ritual and experiential behavior, only the documentation of these actions are presented within the gallery. Calle's work poses a problem for both the critic and the viewer. On the one hand, her dry presentations—marked by an documenter's indifference and often consisting of unremarkable photographs alongside framed texts—exhibit a cool, formal distance that deflect emotional attachment. On the other hand, the subject of Calle's work is often autobiographical and extremely personal, inviting a false sense of intimacy shared between the artist and viewer. It is for this reason that Robert Storr cited the "forensic qualities" of her work and Donald Kuspit accused Calle of being nihilist. It is this point of tension that also inspires many critics (including Kuspit) to use the word "seduction" to discuss her work. It is also for this reason that one of the subjects (or some might say victims) of Calle's intrepid documentary impulses was so angry that he published a nude picture of the artist in a widely circulated French newspaper. Yet a young Parisian fan of Calle's work was so inspired that she presented Calle with her personal diary after meeting her at an opening. Calle's work indeed seduces, with its obsessive documentary urges that lure the voyeur in us all. Exquisite Pain—on view at the Portland Art Museum thanks to the very exciting Miller Meigs Endowment of Contemporary Art—provides a nice cross-section of the concerns that re-appear in the artist's work again and again. Early work from the 80s, like Follow Me (Suite Venitienne) or The Shadow (Detective) activate and investigate urban spaces in a way that very much finds roots in the Situationist wanderings of Guy Debord and the 19th century figure of the flâneur. Other pieces go to great lengths to involve the habitants of these urban spaces, and many of Calle's pieces solicit stories from strangers through interviews. Throughout her career, Calle's work has returned to unforgiving inquiry into the artist's own behavior, either by her willingness to engage in rituals that later become the central focus of her art projects or by categorical examination of psychologically or emotionally complex situations. Exquisite Pain tracks Calle through a psychological journey through a three month period of intense sadness, chronicling the passage of grief after a relationship was abruptly ended. She tails her own pain in the same way that she tracked strangers on the street in the early 80s. In late 1984, Calle left Paris to complete a 3 month residency in Japan. Involved in a new and passionate relationship, she spent the entire time in anticipation of the reunion with her lover, which was to take place in New Delhi on her way back from Japan. After arriving, Calle learned that her lover would not be joining her because he had found someone else. Racked with pain, Calle spent nearly three months afterwards in a systematic ritual of telling and re-telling her story to friends, acquaintances and "chance encounters" in order to slowly relieve herself of the pain. In the process, she also began soliciting stories from the people she talked to, asking each one the question, "When did you suffer most?"

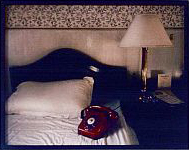

It wasn't until fifteen years later that Calle was able to approach this subject matter again through her artwork, creating a series of framed diptychs representing each day of the approximately three month period of suffering. Calle's story is documented through embroidered lettering on fabric, her story written again and again, each with slightly different nuances and each time accompanied by a photograph of the red telephone in the shabby hotel room where Calle received the devastating news. Alongside each rendition of Calle's story is a story from a stranger, accompanied by an emblematic photograph of their own story. Although not exhibited at the Portland Art Museum, the original installation was also accompanied by a collection of ephemera from her travels in Japan, creating a symmetric documentation of the approximately three month period of time leading up to the breakup to complement documentation of the aftermath. Autobiographical and introspective work is tricky because it turns self-indulgent so easily. Calle finds a delicate balance with her own work because of the systematic way in which she documents her pieces. Although the project served theraputic purposes for Calle, there remains a healthy dose of skepticism and distrust of her own emotional reactions, allowing her to retain distance. The consistency of her documentation creates a structure of logic to complement the obsessive and irrational nature of her introspection. The thread embroidering Calle's work becomes increasingly darker over time, until her story nearly fades away into the charcoal-colored fabric onto which the letters are embroidered, reflecting Calle's process of recovery and objectification over time. In contrast, the stories of Calle's friends and acquaintances are embroidered in dark thread on white fabric, each bearing the same stark intensity. In the first several days, Calle's explanation is long and detailed, focusing on the long period of anticipation leading up to the expected reunion and shocking news. Intimate details come forth. The viewer learns that the unnamed lover,"M," didn't simply leave news of his breakup, but greeted Calle with a cryptic message at the hotel about being in the hospital. After hours of unsuccessfully trying to phone home for news and imagining the worst, Calle learns that "M" has in fact simply cut his finger, and the message is in fact a cowardly breakup note. As the days and the stories progress, Calle's renditions turn to nostalgia— "M," is her father's friend, and Calle remembers having an attraction for him even as a young girl—and then to regret and bitterness. She derides herself for pinning such hopes on the relationship during the her separation in Japan, citing this as the reason for the intensity of her pain during the breakup. Over time, her stories become increasingly shorter, more factual and analytical. Calle's pain seems to fade away in part because of the cumulative magnitude of the stories of loss and pain revealed by those around her, many revolving around the death of a parent, friend or lover. On day 58, the story is proceeded by a disclaimer that "It's an ordinary story, yet I had never suffered so badly before." The last panel, ends with a simple, exclamatory, "Enough." Through February 12 • Jubitz Center for Modern and Contemporary Art Posted by Katherine Bovee on February 07, 2006 at 9:18 | Comments (1) Comments Upon first seeing Calle's work, I was completely enthralled. There is nothing more attractive than this voyuerism of one's life and pain. Just look at how much the American public loves "reality" TV. However, the problem I have with her work are the problems you already described. Her diptychs feel cold. Which in turn makes it difficult for you to follow through and read every panel, unless you are very devoted to doing so. I was interested because the elusive stories themselves were fantastic. Yet I can see how many would maybe read one, and just get bored because of the works' presentation. I still love the work, but I can definitely see how it is either a love or hate kind of series. Enough. Posted by: Calvin Carl Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |

![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.portlandart.net/nav-commenters.gif)