|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

Hans Holbein's Madonna of Mercy at PAM

The Madonna of Mercy I would like to propose the argument that Hans Holbein the Younger's Madonna of Mercy (Portrait of Jacob Meyer and family), currently on view at the Portland Art Museum as part of the Hesse collection, is a far more significant work than the Mona Lisa. The Mona Lisa is an incredible singular point in the canon of Art History. It is a small window through which a vast expanse can be perceived. The alien landscape of the Mona Lisa represents the vast consciousness of the archetypal genius of its maker, Leonardo. The crux of my argument is that the significance of the Mona Lisa depends on the idea of "artistic genius". Although this is an idea we have become fairly comfortable with in negotiating the work of Renaissance artists, it is an idea which emerged fairly recently, and was carefully crafted for a specialized purpose. Leonardo is the prototype for our ideas about the genius archetype, but the full elucidation of this idea didn't even occur until 1867, when Walter Pater developed the criticism that made the Mona Lisa famous. In fact, it was not really well known until that point, and considered a minor work of the High Renaissance. Walter Pater's 1867 essay on Leonardo established a cult following around the painting. Pater's writing is mystical, dreamlike, more related to poetry than analysis. Pater describes the figure as a mythic embodiment of the eternal feminine, "older than the rocks among which she sits" he even goes so far as to liken her to a vampire, a creature who has transcended death and "has been dead many times and learned the secrets of the grave" It is notable that Pater's metaphor of the vampire is due in part to the deterioration of Leonardo's pigments. Leonardo, always experimenting, was known to use unusual organic compounds in creating support grounds and varnishes. The Mona Lisa rapidly discolored in the years after it was executed and the vibrant skin tones Leonardo expressed in the original painting took on the greenish pallor we are today familiar with. The sickly color of her skin contributed to Pater's poetic metaphor of the vampire. Clearly Pater's supposedly art-critical thinking functions better as autonomous poetry than analysis. But Pater's ideas were accepted and became the historical truth. Artists and historians loved the idea of the artistic genius, and found it backwards compatible in a diversity of biographies. We now had a language for addressing the role of personality as an emanation of artistic practice, modeled on Leonardo. His mysterious secretiveness and bizarre interiorality could now be explained. The hostile, unpleasant and acerbic personality of Vincent Van Gogh could now be rediscovered as a quality of artistic genius. Picasso's loud-mouthed bombast and dynamic charisma easily fit into this architecture, and the important relationship between Picasso's social persona and the Mona Lisa was exquisitely illustrated when he and Apollinaire were detained for questioning after its theft in 1911. We even use this framework to explain Pollock's alcoholism. But of course, we have no such oppositional guiding principle that explains why Monet was a gourmet chef, or why John Cage was also an authoritative mycologist!

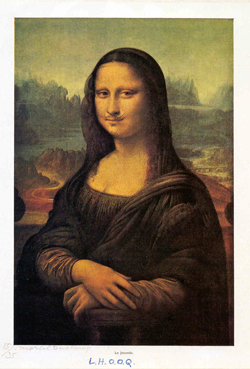

Marcel Duchamp L.H.O.O.Q. Pater's poetry describing the eternal feminine was reiterated over and over, ad infinitum. Duchamp sexually complicated the Mona Lisa with his sly joke, L.H.O.O.Q. in which he simply drew a mustache and beard on a postcard of the image. In pop culture Dan Brown synthesized Umberto Eco and simplified and reconstructed Pater's poetry as "clues" in his Grishamesque "Da Vinci Code". Since this detective story is now in production in Hollywood, this means Pater's sexualized deification of the Mona Lisa will now be immortalized in film! Subtly attached to Pater's ideas of the eternal feminine, is the more significant idea, one so thoroughly assimilated into the continuity of the Canon as to become totally obfuscated: the idea of the artistic genius. The great comic irony of the history of this idea is that it is now applied even to Duchamp, who was its most outspoken, vitriolic and prankish critic. In the shadow cast over Art History by this idea there is the biography of Hans Holbein the Younger. Holbein was not lost in his own alien interior world, as Leonardo was, but a masterful painter who worked dutifully in the service of his patrons. He lived during the explosive times of the Protestant Reformation, and his work reflects the experience of those times, and their impact on the individual. Leonardo constructed barriers which insulated his artistic practice against socio-political events, but Holbein's practice was always directed by his patrons, and therefore, a better reflection of the times in which he lived than Leonardo's work. Holbein worked on both sides of the Reformation, for whomever would employ him. He created portraits of Catholics and Protestants. He worked both in the households of Humanist Aristocrats and the tyrant Henry the VIII. He composed portraits both of the Swiss moneylender Jacob Meyer and his family and the great Scholar Erasmus. Hans Holbein was a stylistic virtuoso, with such authoritative command of the relatively new media of Oil Paint that he could simultaneously work in multiple styles, flawlessly emulating the glowing Italianate Classicism as well as the more photographic hyper-detailed Northern Style. Indeed, in the Madonna of Mercy both of these styles coexist without integration! The softly glowing Italianate style cuts a swath through the center of the picture, enshrouding the biblical figures in a hazy, luminous aura. The portraits of Jacob Meyer and his family are rendered with photographic naturalism in the harsher, more detailed Northern Style. This non-integrated stylistic disjunction creates a circuit of tension between the real and the sublime. Jacob Meyer, the Catholic, and his family are un-forgivingly scrutinized. Every detail is meticulously re-created. One experiences the different fabrics of their garments as tactile sensations, even Meyer's skin is rendered with unflinching tactile acuity. The taut skin of his forehead has a different feeling than the weathered skin of his hands, and even the grain of Meyer's beard stubble is readable in the Northern style. By contrast the biblical figures are luminous and homogenized. They glow from within and the surface of their skin is soft and buttery. Mary wears an ornate gold crown, which in light of the revolutionary times, seems a feeble assertion of the dwindling political power of the Orthodoxy. Northern elements have infiltrated the depiction of the Queen of Heaven. Mary is not garbed in light blue Italian silks, but rather wears a heavy black and gold robe with a long red (silk?) sash around her waist. At this point, I need to take a quick aside, and mention the impact of this detail on my class! Debate raged about the significance of this single element! It was something I didn't attach a lot of importance to, but the possibilities of interpretation seemed endlessly fascinating to my students, and they delighted in generating one hypothesis after another. For instance, is Mary's sash symbolic of her marriage to the Divine? One student suggested that because of its vivid color, it was a symbolic prefiguration of the crucifixion. Another suggested that it symbolized Mary as the link between the spiritual world and the real world, like a rope connecting the two. This is a well crafted idea, as Mary is often thought of as a conduit between the Human and the Divine, for she remained human even as she became a vessel for the Divine. However, I have been unable to support a definitive reading of the meaning of Mary's sash through research. If one was able to produce a document describing Northern Renaissance marriage practices involving a red sash, then perhaps one of these hypotheses could be proven. My students seem much more excited about this symbol than I am, so I will leave it them (or Port Readers) to do this research.

Holbein's portrait of Thomas More, 1527 This was Holbein's last major religious commission. He would go on to abandon his family in Basel and join the household of the great humanist thinker, Sir Thomas More in 1526. Thomas More of course, created one of the most significant ideas in cultural thinking, one that has continued impact on art and society. Thomas More invented the idea of Utopia. A Utopia (antonym Dystopia) is an imagined place or state of being in which everything is perfect, or somewhere else that is better than this place. As Louis Marin has noted, Utopian impulse is the central dynamic underlying all of Modernism! Remember that the goal of Modernism was to find the perfect, purified form of every mode of creating art! The goal was to perfect the art of painting by removing illusionistic tendencies related to photography; or to perfect sculpture by removing tendencies relating to painting, (like color). Of course the end result of this reduction was minimalism. It is a fine and distinct detail to note that in crafting his term, More didn't use a prefix which meant perfection. The word Utopia comes from the Greek "ou + topia". Topia meaning place and the Greek "ou" meaning "not". So even in the craft of his idea, More acknowledged that his perfect place was not real. And yet, why didn't he simply use the term Outopia? By truncating the prefix, More suggested that a Utopia is not a real place, but a possible place! A place that could be made to exist. A place not yet real. Clearly Utopian ideals chart the course of Modernism, but I would venture the argument that Utopian impulse underlies art practice itself. For what is art if not the realization of a possible world which does not yet exist? Art is in fact, the intrusion of the possible into the probable, the experience of the liminal in the midst of the quotidian, or the reintroduction of the quotidian as liminal experience. Jacob Meyer, as I have mentioned, had remained true to the Catholic cause in the midst of the turmoil of the Reformation. During the years Holbein was working on the painting, Meyer was the leader of an orthodox group barely holding out against the revolution; just clinging to solvency. Holbein would have no more commissions with religious subject matter because of the Protestant iconoclasm! Protestant revolutionaries were destroying images all over Europe. Although Luther himself considered iconoclasm a waste of time and wrote that in his new version of belief, all Christians were accountable to the law, for the most part the populace took it upon themselves to tear apart the symbols of religious authoritarianism which favored the wealthy. The Protestant iconoclasm made Europe a cultural wasteland. As with all revolutions, the radical humanists whose ideas had begun the revolution became gradually excluded in favor of a mindless leveling destruction. Somehow, Meyer commissioned the Madonna of Mercy in this cultural backdrop, and preserved the finished work from obliteration.

Double Portrait of Jacob Meyer and Dorthea on the occasion of Meyer's election as the Mayor of Basel Holbein's portraits of his orthodox patron and his second wife twelve years earlier tell a much different story. Here we see the Pre-Reformation Jacob Meyer of 1516, a wealthy and content moneylender. The double portrait had been commissioned to commemorate the event of Meyer's election as the first bourgeois mayor of Basel. We see a wealthy and worldly man and his wife. In his left hand Meyer holds a coin, symbolic of his economic command. The background is a Renaissance Loggia with a barrel vault which transfers its gravitas and permanence to the importance of the sitters. In comparing the 1516 double portrait to the Madonna of Mercy striking differences become readily apparent. Jacob Meyer and his second wife Dorthea appear much healthier in the earlier double portrait. By the time of the Madonna of Mercy, they have lost significant weight! Meyer's casual, confident sense of command has been replaced by the desperation of an orthodox Catholic tenuously holding out against the sweeping change of the Reformation. In the Madonna of Mercy his hands are tightly clasped, his gaunt face staring vacantly upward in supplication. He is begging the Queen of Heaven to protect him and his family. He has been true to the Orthodoxy all this time, and turns now to those ideals for protection. As one student observed, strangely, Meyer's upward gaze isn't even directed towards the Queen of Heaven, but looks out of the picture plane towards a point on the ceiling above the head of the viewer on a long diagonal. This is perhaps a theatrical illusion. As in theatre, an actor placed upstage of someone they are involved in conversation with will not turn fully around to participate in the conversation, but rather imagine the actor they are speaking to is instead in front them. That way the audience can see the face of both actors at the same time. If Jacob Meyer were to actually look at the Madonna, he would have to turn his back to the picture plane, thus ruining the portrait. The Reformation originated in Germany, facilitated by the new invention of the printing press, and the Northern Style of the early 1500s reflects Reformation ideals. The Reformation framed belief within the structure of the real, observable, social and economic world. Luther called upon Christians to address social and economic ills, to strive towards good government and responsible citizenship. He attacked Church doctrine which favored the rich, and was excommunicated. The church's sale of indulgences or forgiveness for sins meant essentially that the wealthy could buy their way into heaven, while those who could not afford the purchase were damned. Luther's goals of reframing religious ideals so that they honestly addressed the problems of the real world are made clear by his own words: "If you are a preacher of mercy, do not preach on imaginary but the true mercy. If the mercy is true, you must therefore bear the true, not an imaginary sin. God does not save those who are only imaginary sinners. Be a sinner, and let your sins be strong, but let your trust in Christ be stronger, and rejoice in Christ who is the victor over sin, death and the world. We will commit sins while we are here, for this life is not a place where justice resides.. We, however, says Peter (2 Peter 3:13) are looking forward to a new heaven and a new earth where justice will reign." (Martin Luther, in response to a question posed by humanist Philipp Melanchthon) Luther's defiance was a very real sin, a strong sin, for which he needed a very real forgiveness, one which could not be provided by the selling of an indulgence. Luther and his followers felt that sin was necessary in pursuit of real social and economic justice. Holbein is the most important painter who embodies Reformation ideals in his style and imagery. He paints nearly photographically, with meticulous scrutiny paid to every detail, both beauty and blemishes. Holbein focuses intently on the real appearance of his surroundings, just as Reformers unapologetically addressed the ills of their real socio-political environment, and looked toward creating a new earth in which justice would reign. Reformers discarded the abstract ideals of religion in favor of the truth of their surroundings. Holbein's mastery of the Northern style told the truth of his surroundings. Pictures of the Madonna were usually painted as protection for the patron and his family against the plague and natural disasters, but in the case of the Madonna of Mercy, the patron wishes for protection from the Protestant Revolutionaries! Jacob Meyer and his family are rendered in the Northern style, they are living in a reality defined by the Reformation but appealing to abstract ideals of the Orthodoxy, even as those ideals are vanishing. The Madonna and Child are luminous and Italianate, a visual embodiment of the abstraction of the Orthodoxy. The style itself, which Holbein adopts with fluidity and authority, represents the central truths of the Orthodoxy: That religious ideals exist beyond the real in a state of abstract separation. Social, political and economic justice in the real world are not the provenance of the Kingdom of Heaven. The Kingdom of Heaven instead represents an ideal which the real world must conform to, through the dictates of the Roman Orthodoxy. So Jacob Meyer, a man of the times of the Reformation, pleads to the abstract ideals of the Orthodoxy even as they disintegrate. This painting is a liminal object, a threshold. It charts the transition of cultural consciousness in the time of the Reformation. It shows the reality of the Reformation and the perfect abstraction of the Orthodoxy existing in the same liminal space. Although the difference is marked, we see Jacob Meyer, staring through the ceiling above our heads, trying to move through the gap, back into the effulgent world of the Orthodoxy, but hopelessly anchored to the reality of the Reformation depicted by the Northern Style. I think one of the strangest parts of this painting is a detail which at first seems insignificant. This is the carpet. Holbein uses deep shadows to create a separate field for the Madonna and Child which repels the Northern portraits of Meyer and his family. He consciously constructs a dark envelope of space as a barrier between the two, and Northern and Classicizing elements remain unmixed. However, this separation breaks down in the carpet! Both the Italianate figures and the Northern figures share footing on the carpet. The carpet itself exhibits both Northern scrutiny and Italian luminosity. You can see every individual fiber within the pattern in excruciating detail, but all of the colors seem far too bright! You would expect more shadows on the floor, but instead the carpet seems to have the same radiant quality as the Madonna herself! Perhaps because this object had no symbolic weight of its own, it allowed Holbein to further experiment with his stylistic fluidity. He could easily switch between styles, but in this seemingly unimportant detail, he combines them! Leonardo's Madonna of the Rocks (Detail) 1485 Directly in front of Jacob Meyer there are two boys, one a young teen and the other an infant. The text I provided my class described these boys as Meyer's two sons. My class however, in viewing the painting, would not accept this view. If they are Meyer's sons, why are they painted in the same Italianate style as the Madonna and Child? Why do the hand gestures of Meyer's infant son and Jesus seem to correspond? My students brought up the intricate interrelationship of hand gestures between the angel, the infant John the Baptist, and the infant Jesus in Leonardo's Madonna of the Rocks, and it turned out that their observations and dismantling of the accepted knowledge were exactly to the point. The idea that the two boys are the sons of Jacob Meyer represented the old thinking which had recently been dismantled by the same questions my students were asking. As I was desperately riffling through the text in order to rebuff their questions, the docent described how the thinking had changed. It had happened precisely as my students had intuited. Through comparison to Leonardo's Madonna of the Rocks, the infant had become identified with John the Baptist while the older boy had become the guiding angel. On the Madonna's left are the female members of Jacob Meyer's family. In profile we see Meyer's first wife, Magdalen Baer who had died in 1511, and who must have been painted in 1525 by verbal descriptions Meyer gave to Holbein! The presence of the deceased in the painting is an intensification of Orthodox Catholic ideals. Meyer's supplication is for the living as well as the dead. In three-quarter view we see another portrait of Dorthea, her face considerably thinner since the double portrait of twelve years earlier. Her expression is introspective and concerned. Kneeling in the foreground is Meyer's daughter Anna. The painting itself is dated based on Anna's hairstyle, as she wears the maiden's braid and hairband, a symbol of betrothal. Since Anna was married in 1530, we are able to place the dates of the execution of the painting within the 5 years before 1530.

Holbein's portrait of his wife and two children, 1528 In these same years, Holbein was preparing to move permanently to England, totally abandoning his family in Switzerland. He was leaving to join the household of the great humanist thinker, Thomas More. He painted a startling portrait of his wife and two children before he left. This painting is one of the most compassionate images in art history as well as, paradoxically, one of the most inhuman. Holbein captures the sorrow of his family as he leaves for England, they have been crying often, they are to endure a permanent and significant loss as he abandons them to their fate. He observes their suffering in the Northern Style, in the way of the Reformation, with unflinching, meticulous scrutiny. He spares no detail of their anguish. Ultimately, the detachment of his photographic representation reveals the inhumanity of the image. It is not an image of compassion, it is instead a detached visual analysis.

Holbein's self portrait This image is one of the sources of insight into Holbein as a person. He is described as being meticulously objective and detached. I see Holbein as a product of revolutionary times. Just as Jacob Meyer found himself clinging to the fading Orthodoxy as the Reformation demanded justice in the real world, Holbein himself was torn between worlds. His painting was an objective practice, an aesthetic orthodoxy, and he followed it out of the real world and away from his responsibilities and connections. Was Hans Holbein an ideologue willing to sacrifice anything in support of More's radical humanism? Did Holbein abandon everything to become a citizen of More's Utopia, the Not-place which could yet become real? Absolutely not. He worked for Henry the VIII in the exact same capacity that he served Thomas More. Holbein's personal Orthodoxy of objectivity never altered, and separated him from the world in the same way that Jacob Meyer was separated from his Madonna of Mercy. Ultimately, Hans Holbein cannot be considered a citizen of More's Utopia. He lived instead in the Outopia, the not-place which can never be made real. And yet it is this profound detachment, this separation from life, this dedication to the Orthodoxy of observation and meticulous visual recording that makes Holbein's Madonna a profound record of its time. In the Mona Lisa we see the reflection of a singular mind, one deep moment of experience, while in Holbein's Madonna of Mercy we see a record of a generation of experience, and the complex and conflicted interaction of a divided and changing society. Posted by Isaac Peterson on February 20, 2006 at 6:56 | Comments (5) Comments It is interesting how the public considers the Mona Lisa such an icon, and we all agree it is a lovely painting, but none of us really know why we are supposed to love it so much. It is somewhat like a war that has neither a beginning nor an end, and you still keep fighting because that is what your ancestors did. Posted by: Calvin Carl I can understand why people would want to say that Holbein's portrait of his wife and children is inhuman. What kind of a man leaves his family to fend for themselves in Switzerland while he traipses off to England never to return? What kind of man indeed? The kind of man who paints portraits of his family with such sorrow in their eyes to remember them by? I do not think that such a man could revel in their misery when he had endured so much of his own. Revolution is never a pretty thing, a hardship to endure amoung other woes of daily life. But perhaps by accusing Holbien of abandonment we give him too little credit. I do not know whether Holbein was a rich man but he may well have had the means to transport his small family to England. Perhaps he and his wife had discussed the subject at length and had decided that she wouldn't go because she didn't want to abandon HER family. Perhaps she was to be taken in by relatives or perhaps she thought she would fare better to stay and marry another man. Posted by: Hallie Chilton I'm not sure if the whole story is known! It may have been as you describe, some kind of agreement between them... What the painting attests to is their suffering... perhaps the context is lost? Posted by: Isaac I wish Emily Baxter, Tweek or Alyson would write a comment about Holbein's Christ in the Tomb.... I didn't even start on it! Posted by: Isaac Chelan Hendricks- I would like to comment on my recent interest relating to the Mona Lisa. Why she has been the center of the art world’s focus for so many years has always baffled me. Out of the renaissance came a much vaster array of artistic genius and it is to my belief that the Mona Lisa can hardly be classified as this. I admit my judgment may be partially influenced by the over saturation of this painting. Imagine never experiencing the site of your own face and then you look into a mirror for the first time, what a shocking and amazing experience this would be! If I had never viewed the Mona Lisa and saw it in person for the first time my feelings for the piece could possibly be a drastic difference, I doubt it but who's to say? However, thanks to Mr. Pater my eyes have been opened to an aspect of the piece that I had not yet considered. Despite my prior feelings the painting is now actually interesting. The way Pater describes the Mona Lisa as being a vampiric idea of eternality is both mystical yet justifiable. Leonardo’s landscapes alone speak of an eternal land. A place that is long gone yet still present. The Mona Lisa herself as a vampire is a unique perspective. What is a vampire? It is the eternality of human life yet not played out through heaven or hell. The vampires are instead left to walk this ungrateful earth forever. “The punishment of selfish desire” as Anne Rice puts it. I believe vampires mean more than monsters walking the night on the hunt for innocent blood, it is our inability to accept what is, fate of ourselves or others, laws of this world, consequences of our actions. A vampire is everything that we refuse it is what we will not let rest it is our way of rebelling against nature. Leonardo refused to accept the common knowledge of the world around him. He rebelled against nature and fought to learn its secrets and he did. What would Divinci be if he did not learn everything he possibly could? He would be a dead man with lost paintings. The Mona Lisa was Divinci’s vampire, no wonder there is a mystery in her smile. Posted by: Chelan Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |

![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.portlandart.net/nav-commenters.gif)