|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

Report from France (Part I)

The illustration for the 2005 Lyon Biennial seems as if it is lifted from a 60s or 70s sci-fi book cover. Against a paint-splattered psychedelic sky, the silhouettes of three men turn to face a gigantic planetary orb rising above the skyline. It's an image that captures a moment of discovery - the discovery of alien planets, foreign terrains and spectacular sights. It illustrates exactly the kinds of reactions one is hard pressed to find within museum or gallery walls these days. In a time when cynicism and re-appropriation reigns, it's rare to find newness or impact. I was in France for the holidays, traveling to see the last week of the biennial and catching several shows in Paris. As expected, I saw very little that was truly new or awe-inspiring [disclaimer: I can't blame France's art scene entirely, since many galleries were between the major exhibitions of last fall and a round of new exhibition opening in mid-January]. But I did see a new kind of crisis bubbling beneath the surface, one that is sure to influence if not define whatever artistic and curatorial impulses the future holds for us. An obsession with imaginary or re-imagined terrains - physical, psychedelic and real - repeatedly appeared in the work that I saw. It's present not only in France (where nearly half of the gallery artists I happened to see were American), but also in recent U.S. shows like MOCA's Ecstacy. Perhaps against a backdrop of "already been done," artists are trying to reclaim their position as the creator of new aesthetic and intellectual terrain. Or perhaps, if I allow myself to have an utterly cynical moment, it's the curators who are taking on the job of inventing new worlds, conveniently relieving the artist of this "burden." Nature Nature is often at the root of exploration, as science opens up new micro and macro dimensions, but also as human nature provides a continual source of inspiration for inquiry.

At Galerie Emmanuel Perrotin, Naomi Fisher's savage women frolicked amidst lush green flora, apparently situated in somebody's extended fantasy involving tropical islands and hot girls. Her photographs look like high-end fashion shoots that are trying to look like an updated version of campy Italian films. Her drawings feature luridly colored portraits of females with vacuous, blood-red eyes. Fisher plays out taboo fantasies to a highly choreographed end - the hyper-sexed woman, the hysteric woman, the savage woman, the mother-nature-goddess woman. It's not the clichés that are disappointing, it's the fact that they are so highly stylized that they have scarcely more affect than the glossy fashion spreads in wallpaper* that I read on the plane ride to France. The imagined terrains and savage subjects of Dana Schutz far outdo the work of Fisher. It was funny, however, to notice the dramatic strategies shared by Fisher's photographs and the Classically inspired sculpture and reliefs that flanked Perrotin's entryway, depicting dramatically posed figures and scenes of warfare.

John Maeda's Nature at the Fondation Cartier re-imagines nature as a well-spring of abstract pattern from which he draws inspiration for his computer generated designs. Maeda, who is a professor at the MIT Media Laboratory, was one of the first to explore computer programming as a basis for graphic design. Mixing graphic design and art still presents challenges (see ongoing McGuinness commentary) and either Maeda or the exhibition's curators made the unfortunate decision to deem a series of seven flat screens displaying projections of nature-inspired design as "motion paintings." I was thrilled to see a significant show by this deserving designer, but I wish Maeda's projects were just presented for what they are, instead of relying on art-world terms and slick presentation to justify a design-based exhibition.

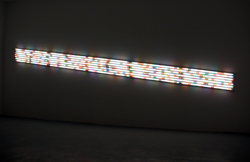

Spencer Finch looks to nature not so much as a source for aesthetic inspiration as for pure data. At Yvon Lambert, Finch continued a series that appears to revisit minimalist light works, but is in fact a very scientific study of light. Using a series of colored gels, Finch alters rods of fluorescent light to mimic the light as measured at a specific locale and time, such as sunset in Texas. For this exhibition, Finch recreated the light outside of the cave of Lascaux, where the famous cave paintings reside. He mimics the nuances of light and color as they would have appeared to paleolithic men coming out of the cave. Listening to an interview with Finch in the gallery's incredible video library of exhibiting artists, I could barely stomach his romanticized musings on the work's reference to the origins of artistic gesture in the caves. But, it's not hard to look past the mushy rhetoric, since his work is at once scientific and sublime.

In opposition to his light work, Finch also presented a series of nearly identical drawings that one learned were meticulously crafted drawings of darkness in the caves. One comment Finch made in the video that did resonate was his explanation of the fact that in many ways, he considers himself to be working in the genre of hyper-realism. It is the play between the presence of highly scientific data and less quantitative qualities like time, nostalgia and memory that provide the key to Finch's art.

Posted by Katherine Bovee on January 23, 2006 at 1:18 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |

Graphic design: Cédric Henry

Graphic design: Cédric Henry Entryway at Galerie Emmanuel Perrotin

Entryway at Galerie Emmanuel Perrotin John Maeda at Fondation Cartier pour l'art contemporain

John Maeda at Fondation Cartier pour l'art contemporain Spencer Finch at Yvon Lambert

Spencer Finch at Yvon Lambert Spencer Finch at Yvon Lambert

Spencer Finch at Yvon Lambert