|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

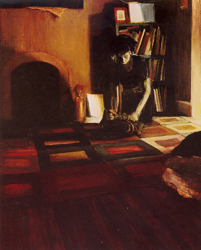

Bundles and Ties Becky Slemmons's show of new paintings at Blackfish is entitled Bundles and Ties. The subject matter is slow and contemplative, but the execution is rapid, luminous and sometimes quite clumsy. Slemmons studies adolescent girls in domestic environments, a world many artists have found charged with sexual potency and dysfunction, but Slemmons's subjects are slow and introspective.

Faith's Preference Bathed in light that is somehow harsh and image-eradicating as well as warm and radiant, young girls in somber dresses bundle cloth into careful, soft objects. The figures are engaged in protective acts, preserving some object to which childhood has fixed undo importance and a heightened sense of fragility. Many of Slemmons's compositions conspicuously feature well-laden bookcases, and the proportions of the bundles lead me to believe the protected objects are books. The strangeness of the activity; the consciousness of the actor totally focused on the irrational task, disconnects the viewer totally from the psychological environment of the painting. The figure is alone in the room, we are witnessing the moment somehow without violating the privacy of the young girl. The consciousness of the girl is free to explore a strange duty, to exist as it naturally is, unchecked by our observation and determination of the normalcy or usefulness of what she is doing. We witness without being physically present, instead perhaps we are psychically present, perhaps through astral projection. One is reminded of Degas, whose keyhole paintings allowed the viewer to witness the introspective consciousness of a single dancer in a private space. However, Degas' brutal lasciviousness simplified a complex interaction into a forceful shove. There was no question as to why the viewer looks through the keyhole. The viewer is a peeping tom. In Slemmons' paintings, the interaction is more complicated. It is difficult to see why we would even be interested in the strange, slow activity taking place. The figures are unaware of our presence, they do not feel the weight of our gaze, and yet there is no differential filter which maintains their privacy and allows us to look (i.e. Degas' keyhole). The viewer is not a voyeur, but rather a free-floating conscious emanation. The viewer is a ghost, or perhaps a cat. Slemmons' mysterious, slow subject matter is counterpointed by her rapid, incendiary brushwork which dissolves the subject into luminous abstraction. The paintings become purely compositional, stacking expanses of unmodulated color beneath complicated lattices of light and dark. Light in the paintings comes from a single, overly intense source, usually from the left or right rather than above, and this further organizes the entire composition along a transversal vector. Following Faith's Preference from left to right, it goes from a dark unified field to an intricate rhythm of bright lights and darks. The tiles or carpet squares on the floor are pushed into single values or anomalous vibrance by Slemmons' generalizing bravado. Slemmons' has pushed on the light until it has become entangled in the materiality of the objects. The light doesn't illuminate the room, it penetrates the objects in the room and changes their properties. The carpet tile nearest the light source becomes bright white, and the next one is bright pink, and the next one is vivid green. Assuming all the carpet tiles in the room are part of the same pattern, as the floor is illuminated it should change in value as a surface, but it doesn't. The tiles flash and change sporadically, they become different objects when they encounter light, they absorb the light as a characteristic, as if they were being stained rather than illuminated. Slemmons' brushwork is full of bravado, yet also discorporated. Sometimes she loses the proportions of the figure or the perspective lines of the room. Mostly the discorporations translate into elegant, flowing abstractions, but other times they just dissipate into meaningless blobs, or hesitant, ill - considered clouds. The intense lighting is a theatrical and dynamic force in many of the compositions, but in others it burns them out. However, I wouldn't recommend Slemmons try to "tighten up" or improve her rendering. Also, the old mechanical figure painter's admonishment, "Never use pure white or black," comes to mind when looking at this work, but I often think "why not?" Because it fractures the composition, because it creates disunity? Because it breaks the facile softness of color cohesion into raucous rhythms? Because it creates a difficult painting, or a naive one? What makes this work so appealing is the dangerous line it walks, the risks these paintings take. Every piece dares dissipation for real expressionism, and the works fall on both sides. Real expressionism requires a great deal of risk or it lapses into the contrivance of becoming self-conscious of the brush stroke: at which point painting begins to ridicule and devour itself. So let half the paintings dissipate into a puff of smoke, the payoff is the ones that remain. In Slemmons's work, they are vigorous, ethereal, with an explosive energy barely constrained by the simple perspective compositions or the soft, slow, introspective activity of the subjects. Through November 26 • Blackfish Gallery 420 NW Ninth Avenue • Portland • OR • 97209 Hours: Tuesday - Sunday • 11-5 • 503•224•2634 Posted by Isaac Peterson on November 15, 2005 at 20:58 | Comments (1) Comments "...perhaps through astral projection." "The viewer is a ghost, or perhaps a cat." "Slemmons' brushwork is full of bravado, yet also discorporated." Ummmm...are you guys on drugs? Posted by: Effey Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |

![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.portlandart.net/nav-commenters.gif)